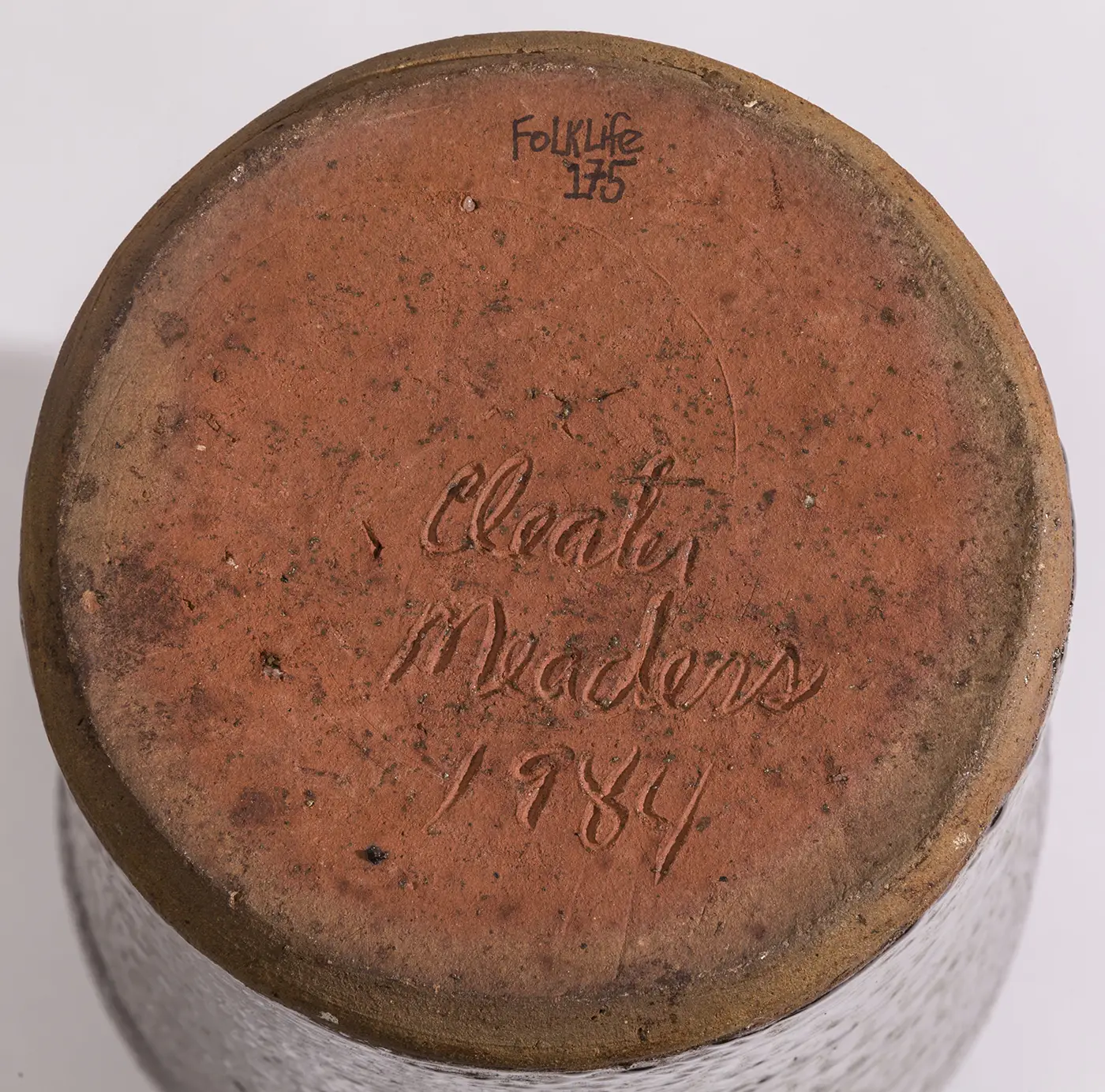

Churn

“Cleater Meaders’s pottery is a wonderful way to highlight not only the work of this important, multi-generation family of Southern potters but also the legacy of Festival co-founder Ralph Rinzler, who was a great admirer of the potters’ skills and a pioneer in bringing national recognition to their work.”

The work of keeping traditional arts alive

In 1983, Cleater Meaders Jr. participated in the second celebration of the National Endowment for the Arts National Heritage Fellows at the Smithsonian Folklife Festival. His cousin, Lanier Meaders, received the fellowship that year, and many in the Meaders family came to the Festival to support him—exemplifying the skill, knowledge, and multigenerational practice behind this distinctive, regional pottery tradition. Cleater made wheel-thrown pots in the crafts tent and talked about making a syrup jug during a filmed segment preserved in the Ralph Rinzler Folklife Archives.

Small-scale family-run potteries grew up in the American South during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The majority of their products were utilitarian: butter churns, whiskey jugs, milk pitchers, food storage jars. The Meaders family, headed by Cleater’s grandfather Cheever, began making stoneware in 1893 in the foothills of White County, Georgia. Making pottery was a way to supplement their farming income and provide storage vessels for themselves. After retiring from a career building aircraft in 1978, Cleater returned to potting full time at his home in Byron, Georgia, where he used an old treadle kick wheel to turn clay he dug from land he owned in the mountains. In 1983, he built a wood-fired kiln on that land, much as his forebears had done nearly a century earlier. The churn shown here was signed and fired in 1984.

Even before his work at the Smithsonian, Ralph Rinzler was an inveterate field worker who kept his eyes open for exemplary traditional artists wherever he traveled. His forays into the southern states exposed him to many regional traditions and fine practitioners who were unknown outside their local communities. Bringing their voices and talents to the broader attention became his passion—and the mission of the Folklife Festival.

It is no accident that Southern potters are so well known today, along with the music of Dewey Balfa and Doc Watson; they were all people Rinzler brought to national attention at the Festival. This work has gone on now for more than fifty years—with the artists front and center: telling their stories, exemplifying excellence in practice, and representing the remarkable diversity of traditional cultural heritage throughout the world.

Postscript: In the summer of 2017, the year we celebrated the Festival’s fiftieth anniversary, we received an unexpected visit from Lena Jackson and her family. Jackson is Cleater Meaders’s granddaughter and had been looking for years for her grandfather’s work in the Smithsonian. She was finally steered our way by her state’s congressional office. The story of their visit is recounted in the Festival Blog.