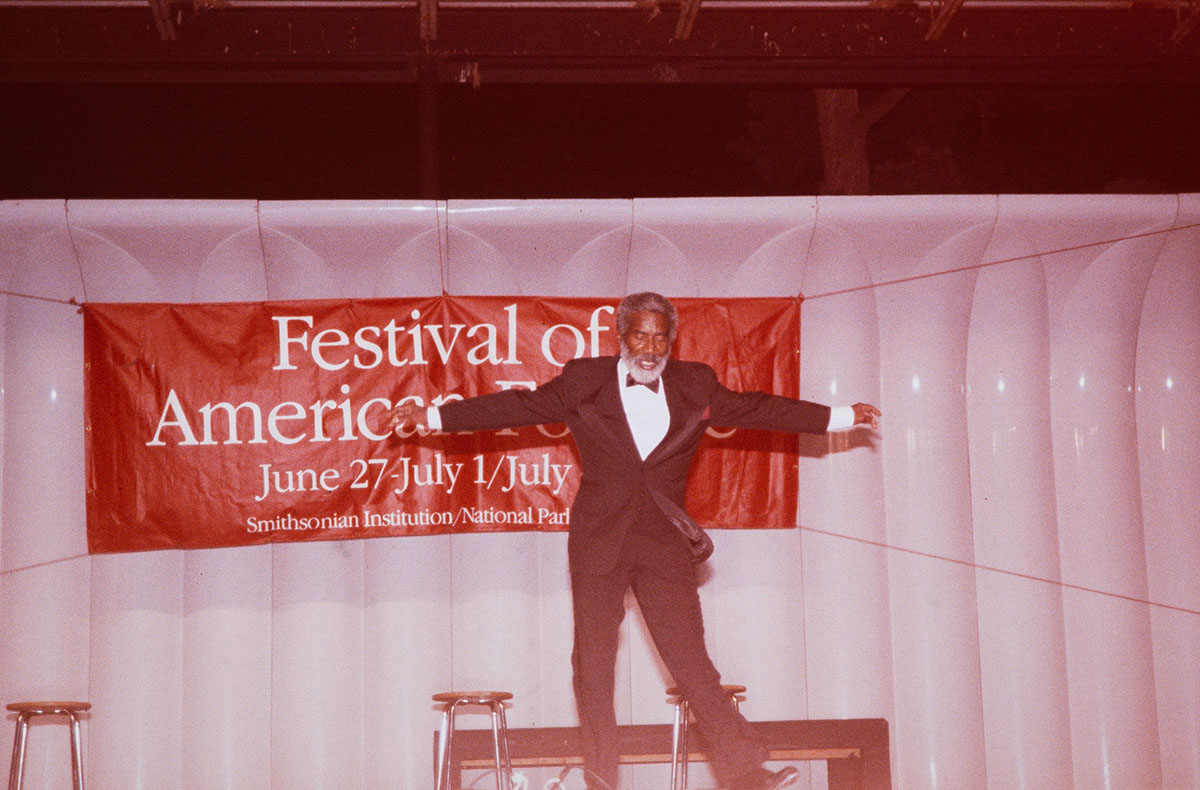

The Festival presentation of black American expressive culture from Philadelphia returned to themes that had animated the African Diaspora programs of the mid-1970s and had later found an institutional home in the Program in Black American Culture in the National Museum of American History. The evanescent Festival presentations, which featured black American folklife since 1967, together with the permanent Museum program, attested to the importance the Smithsonian attached to this aspect of American culture.

Black America began its move to the city because of a driving and desperate need for change. When rural southern communities, for all their fresh air and land, still remained too much a choking, binding, stagnating experience because of racism, economic, social, and political repressions, some people had to leave. In northern cities such as Philadelphia, vibrant black communities took root and thrived.

The rhythm and flavor of black American urban community life take one in many directions. The church served as the first community for the newly arrived family migrating from the rural South. Many urban churches have memberships based on rural congregations. People from Maryland's Eastern Shore, for example, moved into South Philadelphia and into the church that became Tindley Temple United Methodist under the leadership of Charles Albert Tindley, composer of the gospel song, "Stand By Me". Recently, devotional services led by the elders with their old songs in the old traditions have been supplanted by the sounds of gospel songs accompanied by electronic organs or instrumental combos. Today, one finds gospel music in congregations throughout the community regardless of denomination: Baptist, Methodist, Catholic, and Episcopal.

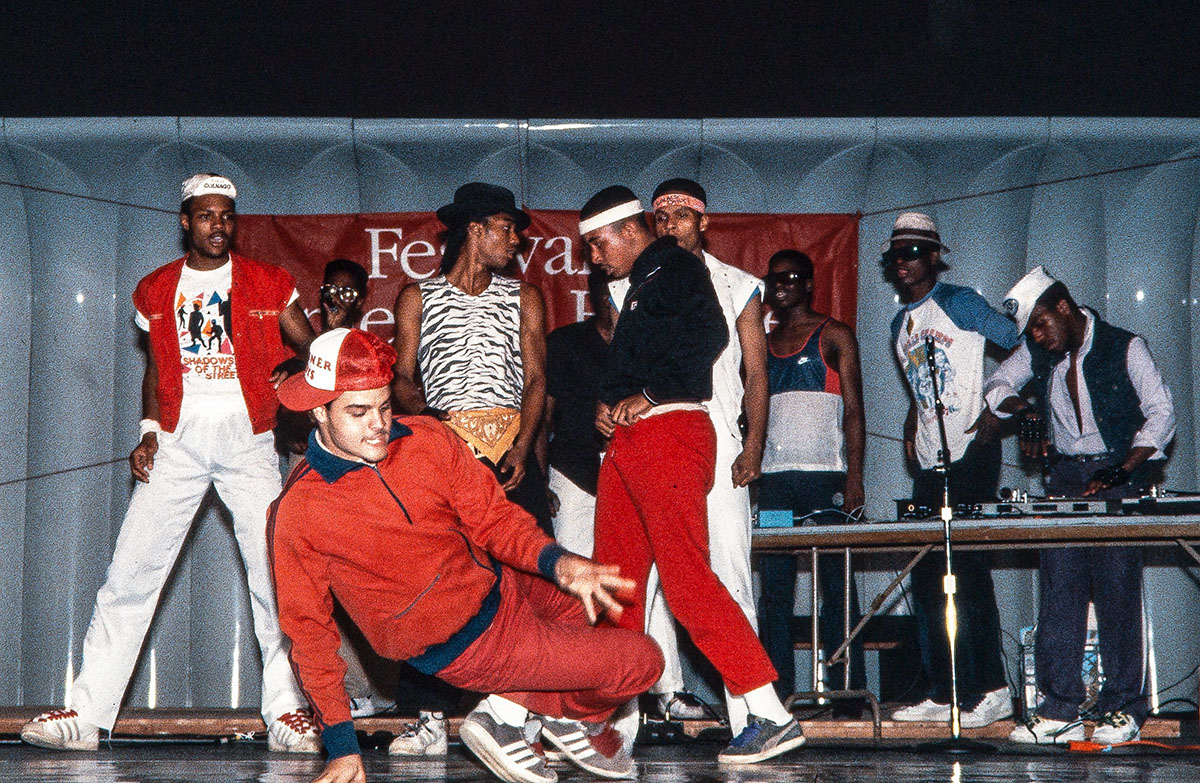

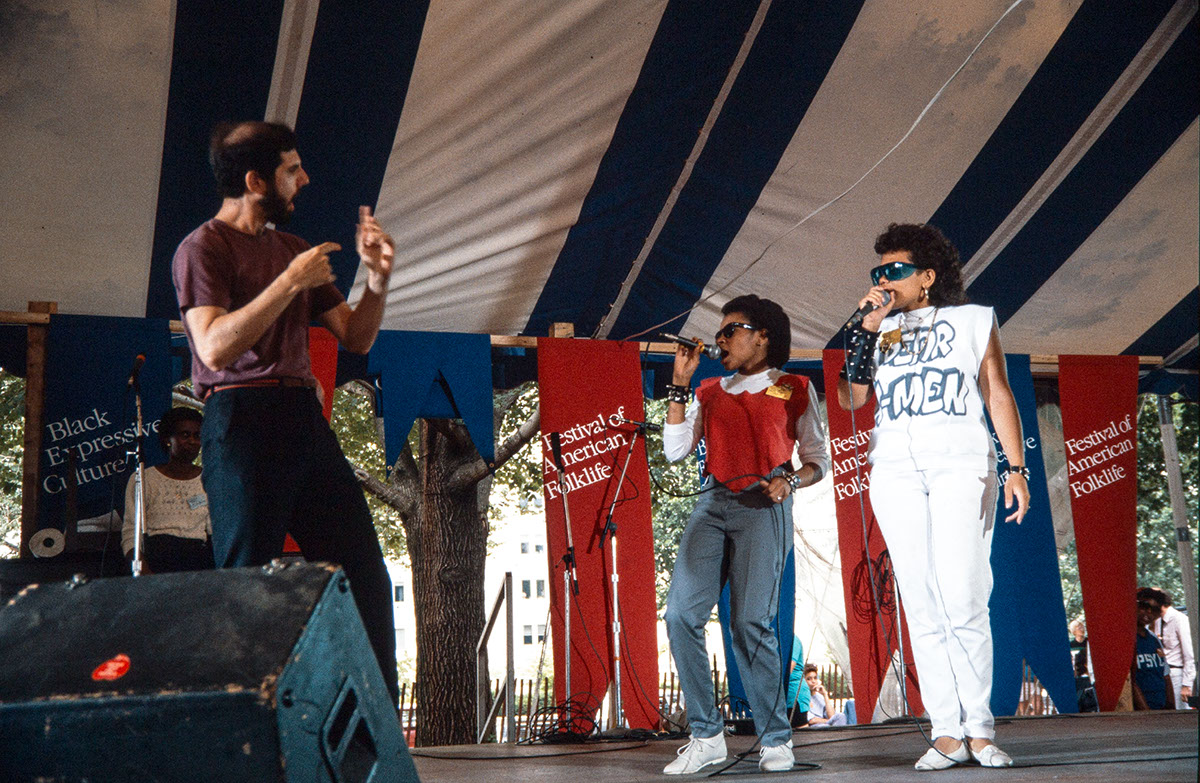

Then there is the home - the row house, the apartment with children who have keys - where the food is still pig feet and collard greens and stewed corn and tomatoes and okra, bought fresh or frozen or sometimes even grown in the garden out back (if there is a back), or down the street (if there are community plots this year). The urban street has no fields, no wide spacious yards - many front porches are stoops on the sidewalk. People sit outside in the evening after work. Children play on the sidewalk. The street also has its music, previously in the form of "do-wops" and now of "rap" groups. With the development of rappers, block bands, and dance groups, the street and sidewalk performance spaces are also basements, park festivals, recreational centers, and street stages.

At the time of the Festival, black American urban culture continued to reflect a community still being born, still in transition, still working out the problems faced by a people once secure in extended families on rural land settlements, then moving in search of a new kind of security, where family, home, church, party, street, and community may be formed far beyond blood lines. The culture of American cities, as presented in the 1984 Philadelphia program, echoed the fact that urban America is also black urban America, a powerful, rich, evolving source of cultural life and creativity.

Kazadi wa Mukuna served as Black Urban Expressive Culture Program Coordinator, and Rose Engelland as Assistant Coordinator.