The 1984 Alaska program offered an opportunity to reflect upon the Smithsonian's involvement with that State. For more than a century, the Institution had devoted a large part of its scholarly effort to the documentation and preservation of the deep and varied cultures of the indigenous peoples of the Americas, including Alaska Natives. The Alaska program also included representatives of occupations whose labor and cultural expression shaped that State in a profound way.

Among Alaska Natives, the old ways, the indigenous arts, reflect long experience in a place. Alaska's traditional Native arts are tremendously varied and rich with meaning, and they are inseparable from Native values - especially a sense of the relatedness of all things - closely tied to the use of local materials, and dependent upon the seasonal rounds of subsistence activities. While traditional materials, processes, and designs are evident in much of the material culture of Alaska's Native people, change is also evident. Power tools and sewing machines shorten and ease tasks. New materials replace old, sometimes by choice, sometimes by economic necessity (beadwork is now often done on felt because a single tanned moosehide may cost four or five hundred dollars), and sometimes because new and complex regulations make access to some materials, such as birchbark, difficult. In addition, side by side with the traditional artists, a generation of contemporary artists are creating new idioms for Native art. Among Eskimos, Indians and Aleuts, art has not been seen as a separate category of life or as an inventory of certain objects, but rather as a part of life. It expresses the relatedness of everything in the natural world, the social world, and the spiritual world.

The Native people of Alaska refer to themselves as "the people." "Yupik" means "real person" and "Tlingit" means "human". The oral traditions of all Alaska Natives teach the individual how to be human - to know who one is and how one fits into society and the cosmos. The categories of sacred and profane are perceived in a very different way than in the secular mainstream American world view. Stories and songs allude to each other; both record history, and are often reflected in visual arts, such as Chilkat robes, masks, carved dance headdresses and helmets. Yupik dancing, to take one example, is as vital today as ever in the delta region. Men and women continue to dance to the steady rhythm of the hooped drum, traditionally said to represent the beating heart of the spirits as well as the lively movements of the spirits of men and game over the thin surface of the earth.

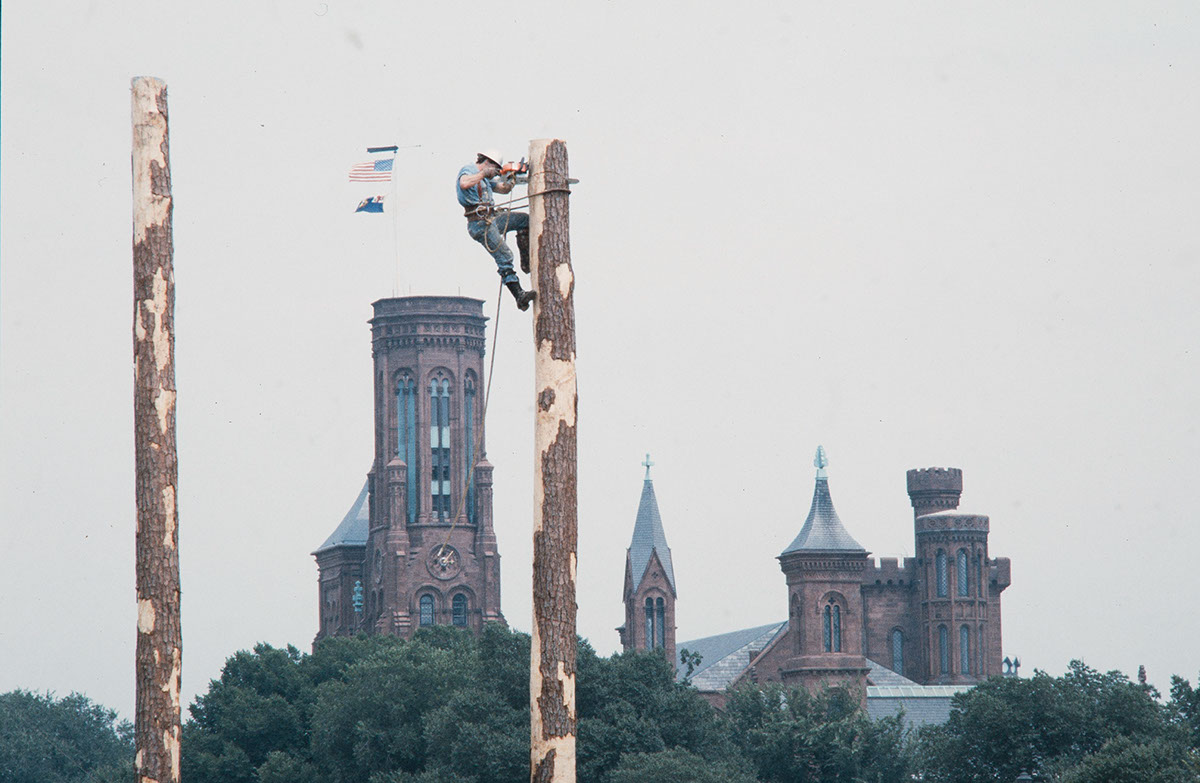

Alaskan occupational traditions give meaning to the world of work. Through these traditions, workers know the history and development of their occupation, share similar feelings about remembered events and people, and learn from the skills and knowledge of experienced hands. Occupational cultures, especially the selected Alaskan traditions presented at the 1984 Festival, also have a second side to them - an outside, in the sense that they have symbolic or heroic meaning for outsiders. The romantic image of the gold miner, the logger, the fisherman and the bush pilot have peopled the popular and literary imagination as symbols of the epic confrontation between society and nature. For Alaskan workers themselves, however, occupational life has more to do with productivity, safety and cameraderie, even though the Alaskan land and sea they earn their living from is, for them and us, among the most dramatically beautiful and valuable on earth.

The 1984 Festival offered visitors the opportunity to encounter the varied traditions of Alaska, with a sizable contingent of Alaska Natives, a glacier transported to the National Mall, and the chance to see its natural bounty - especially fish - transformed into delicious meals.

The Alaska program was made possible by the State of Alaska Department of Commerce and Economic Development through its Division of Tourism and the Alaska Seafood Marketing Institute. Additional funding was made available through private and corporate donations.

Larry Deemer served as Alaska Program Coordinator and Suzi Jones, as Consultant.