The Kumeyaay Communities of California

This year the Folklife Festival focused on resilient communities: groups of people who have survived and thrived through political oppression, forced migration, social discrimination, and more. In Sounds of California, a prime example was the Kumeyaay, a Native tribe that is not likely mentioned in California history books but is quite active around San Diego. Stan Rodriguez, a language teacher at the Kumeyaay Community College and legislator for the Santa Ysabel Tribe of the Iipay Nation, came to Washington with his family to represent the Kumeyaay.

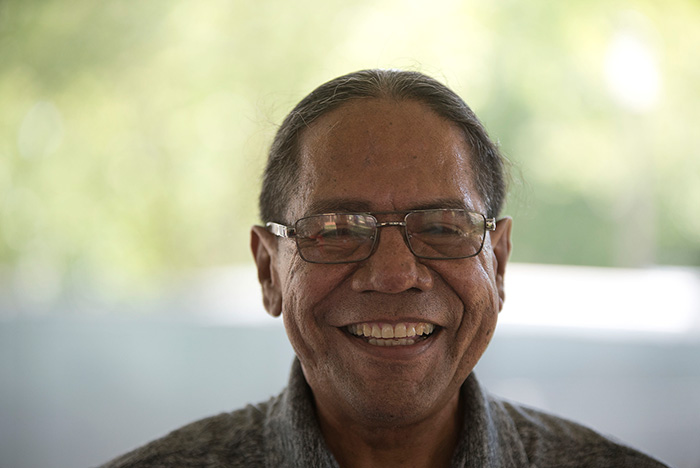

Between Native song and story performances, Stan was busy in The Studio demonstrating Kumeyaay games, making animal traps, knotting cordage into nets, answering questions about his culture, and asking others about theirs. He beamed as a wealth of knowledge and curiosity, encouraging people to research their family lineage and language. A dedicated lifelong learner, Stan is now, at age fifty-eight, earning his doctor of education degree at UC San Diego.

Always eager to share, Stan stepped away from The Studio for a few minutes to explain the history of the Kumeyaay people.

Who are the Kumeyaay?

Our traditional area is from Southern California into Baja California, Mexico. Our tribe is a people of the ocean, the valleys, the mountains, and the desert, all the way to the Colorado River. That has been our territory for thousands and thousands of years.

San Diego has more tribes and more reservations than any other county in the country. We have eighteen reservations in San Diego. Of those eighteen, thirteen are Kumeyaay, and then there’s another five or six in Baja. So the total population prior to contact was over 60,000 people, and now it’s about 4,250.

Our people have been encroached upon first by the Spanish government, then the Mexicans, and then the American government. Diseases took their toll—small pox, measles. It devastated the communities. Warfare took a big part out. We fought against the Spaniards. We burned down the missions. That resistance continued in the Mexican era. San Diego almost fell three time to Kumeyaay forces, but we lost a lot of people.

Right now our tribes, our reservations are starting to recover.

How does the border between the United States and Mexico affect Kumeyaay culture?

It’s very similar to what the Basques talk about. They’re caught between France and Spain. The Basques on the French side speak French and Basque, and on the Spanish side, same thing. We have the same issues. The Kumeyaays in Baja speak Spanish and some of them speak Kumeyaay. The ones in the U.S. speak English and some speak Kumeyaay.

Crossing the border has been difficult, especially after 9/11. Let’s say you’re Kumeyaay from Baja, and I’m Kumeyaay from this side of the border. You want me to go sing over there. Okay, I’ll grab my rattle and I’ll go sing. It’s a little bit easier for me to cross, but now the Mexican government wants Americans to get visas. So now I have to get a visa, I cross into Mexico, I sing, then I come back.

Now for you to come across the border into the United States, you need a “laser visa”—a visa that the Mexican government puts out that gives you the ability to cross the border for six days. The problem with that is it costs money, and most Kumeyaays in Baja live in isolated communities and lack the economic infrastructure to generate that kind of money.

Do you see the culture diverging on either side of the border?

We are Kumeyaay, so that’s the unifying part. The divergent part is they speak Spanish, we speak English, and unless someone speaks both languages, it becomes difficult to communicate.

The survival skills such as pottery making, basket making, food gathering, and hunting with bows and arrows are much more intact in Baja because they are in isolated communities. On the United States side of the border, the religion is much more intact, even though the religion was declared illegal until 1978 when the American Indian Religious Freedom Act was passed.

What makes the Kumeyaay a resilient community?

Even though many people have tried to erase our culture, it is still here. We see our culture as an askay, a pot. This pot holds everything that we are: our religion, our ceremonies, our language—all that we are as a people. When different groups have come encroaching on our communities, they grabbed that pot and they threw it on the ground, and it shattered into many different pieces.

Those pieces are what happened with the Reservation Era, when our tribe was cut in half. It made it difficult for our people. There was a time when we could not just leave the reservations. We had to get a permission slip in order to leave. Rather than be angry at all the things that have happened, we’re getting those pieces and putting them back together. We’re grinding those shards and mixing them with new clay. From there we’re going to make another pot, and that pot is stronger than it was before, because it has the past, it has the present, and it will go on into the future.

Why is it important to teach your culture at the Folklife Festival?

Many people tend to look at the differences we have, and that can be a splitting factor. However, when we come here and share our cultures, we celebrate that diversity. We celebrate the differences. Together we can learn and grow as a people. We can become strong as a people, and not be afraid of others.

I got to see many of the things the Basques are doing and hear about their history and preserving their cultural identity. By sharing that with other people, it makes them stronger, too. And I learned a lot from that. It reaffirmed the belief I have that we’re always students. We’re always learning.

Stan’s Introduction to Kumeyaay Language

Hawka = hello

Eyaay ahan = thank you

Po wim pai yo = that’s the way it is

Kunmuk = let it go

Ha mu yu uy mao ha = yeah, sure, why not?

Ha ho pu yu sa = so? (as a taunt)

Elisa Hough is the editor for the Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage.

The 2016 Sounds of California Smithsonian Folklife Festival program was co-produced with the Alliance for California Traditional Arts, Radio Bilingüe, the Smithsonian Asian Pacific American Center, and the Smithsonian Latino Center.