Names on the Move: The Stories of My Many Names

What’s your name? How many names do you have? What do your names mean?

In May, the Smithsonian Asian Pacific American Center presented a two-day event, CrossLines: A Culture Lab on Intersectionality, in the Arts and Industries Building. It featured over forty artists and scholars exploring the complexity of the American experience today.

I was especially impressed by Brandon Som’s workshop on mapping the intersections within our names and Antoinette Brock’s The Name Project, looking at how names inform self-cognition and drive social interactions. The workshop and project inspired me to rethink my own name changes through the years.

“What’s your name?”

“I have two names. Which one do you want to know?”

This is the typical conversation I have when I first meet someone in this country. Few people realize that I have actually used more than two names.

“Wo jiao DIAO Ying.” My name is DIAO Ying.

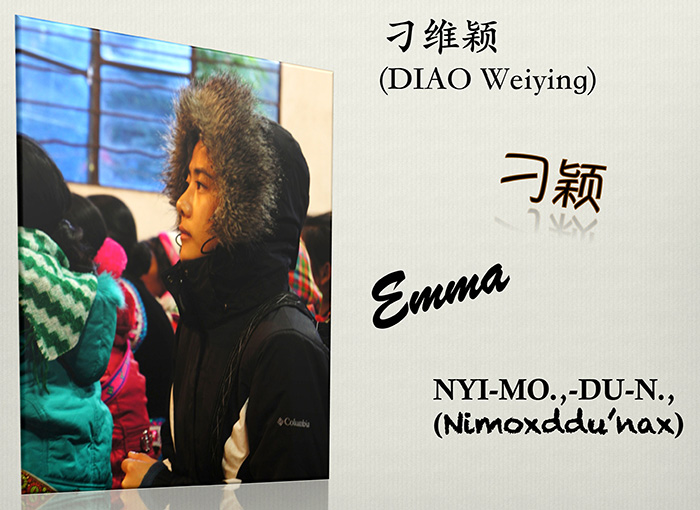

I was born and raised in an ordinary family in China’s southwestern Sichuan Province. My parents named me DIAO Weiying (刁维颖) according to the naming tradition of my paternal family. All of my cousins bearing the surname Diao also shared a Wei in our two-word forename. For example, I was called Wei-Ying and my cousin Wei-Jing.

As I grew older, I found it hard to spend so much time writing the Chinese characters of my given name—eleven strokes in “Wei” and thirteen in “Ying.” So I kept asking my parents to take out the word “Wei,” the symbol specific to my generation. My wish was granted when I turned eight years old: I officially shortened name to “DIAO Ying.” The first name given to me by my parents became a forgotten footnote, largely unknown to most of my acquaintances.

“Just call me Emma.”

I attended Tsinghua University in Beijing for college. During my third year, I studied at Lingnan University in Hong Kong as an exchange student. Every student there used an English name, so I followed suit for more convenient communication. I named myself Emma, as I always loved Jane Austin’s novels, and I was reading Emma at the time.

This name was entirely a product of my effort to “Do as the Hong Kongers do.” I did not realize that it would come in handy five years later when I came to the United States for my Ph.D. studies at the University of Maryland.

Living in a multiethnic country of immigrants, I would not have expected to have problems using my Chinese name. Nevertheless, most non-Chinese speakers usually had difficulty pronouncing my forename “Ying,” either in tone or vowel sound. Very often I had to arduously explain how to say it correctly. I also felt frustrated by people’s confused facial expressions upon hearing my Chinese name.

Shortly afterwards, I just asked everybody to call me Emma for the sake of convenience. In any event, I loved the name. My former colleagues in the ethnomusicology program at Maryland only knew me as “Emma.” This is rather ironic given that, as ethnographers, they were sensitive to the “emic” approach to culture that attempts to understand things from the perspectives of how local people think (in contrast to an “etic” approach that shifts focus to those of the researcher).

“Nguaq Lisu’mi niaq Nimoxddu’nax.” My Lisu name is Nimoxddu’nax.

For my Ph.D. dissertation, I did extensive fieldwork in the northwest of China’s southwestern Yunnan Province on the China-Myanmar border. My research focused on the music making and religious practices of the Lisu people, a transnational ethnic group residing mainly in China, Myanmar, Thailand, and India. Soon after I learned more Lisu vocabulary, I gave myself a Lisu name, Nimoxddu’nax (literally, “daughter of brightness,”) and used it to introduce myself to the local people in token of goodwill, hoping to shorten the distance with them and facilitate conversation.

The responses from my Lisu friends varied: some found it unnecessary, some enjoyed and accepted it, and the others thought it acoustically unlike an authentic Lisu name and tried to give me a new one. I stuck with the name I had chosen because I was drawn to its beautiful sound and rich meanings. Nimoxddu means “brightness” or “light,” indicating hope and guidance—things I felt that I would need to endure the challenges of my fieldwork.

I could also relate the name to my personal life: the sound of the first syllable ni in Chinese is similar to that of my husband’s nickname; the second syllable mo was part of the name Moreland, which I had prepared for my future daughter; and the last nax, meaning the eldest daughter, conforms with my position as the only daughter in my family.

I did not give much thought to my many names until I saw the CrossLines exhibit. I started to jot down a few of my experiences, wrote some more, and then realized that my names had been nourished from different cultures and peoples in the process of my own migrations. Before I knew it, I had written most of this blog.

My name changes have not been the passive outcomes of external influences. Rather, they have been an active driving force in the construction of my identities and relationships with people in different communities with whom I have had close contact.

What is your experience of being “on the move”? Do any of your names reflect this?

Ying Diao recently graduated from the University of Maryland, College Park, with a Ph.D. degree in ethnomusicology. She is currently interning for the Smithsonian Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage and part of the team for the Sounds of California program at the 2016 Folklife Festival.