Groundbreaking Women of the Folklife Festival: 'That Was Then, This Is Now'

Overheard at the 2014 Smithsonian Folklife Festival: “I’m a digital woman, I told you!”

In the intimate, burlap-covered Karibuni Workshops, a discussion of Kenyan string instruments was underway. Its purpose was to introduce visitors to the sounds and performance practices of the obokano and nyatiti, two very similar eight-stringed lyres of western Kenya. The two musicians, Ontiri Bikundo on the obokano and Suzanna Owiyo on the nyatiti, were introduced by William “Tabu” Ogutu Osusa, founder of the Kenyan record label Ketebul Music.

The highlight of their discussion was an impromptu performance by Ontiri and Suzanna (audio below), before which the musicians had a friendly back-and-forth about who should follow whom. Suzanna said, “Ladies first!” and began to sing the apropos lyrics, “Africa woman, arise. I see the power in you. I see the strength in you. Africa woman, arise.”

This setup is very typical of a Folklife Festival demonstration. After the performance, however, it became clear the discussion was going to be about much more than just the instruments when we learned that Suzanna was among the first Kenyan women to the play the nyatiti, an instrument traditionally performed only by men. Not only was it considered taboo, but at one time it was also believed to bring infertility if a woman even touched the instrument.

“Ontiri,” Tabu said, “last time I remember we were having a discussion here, and you told us that women are not allowed to play this instrument. You never really gave a satisfactory [explanation].”

Silence.

With a cheeky smile and sideways glance toward his female colleague, Ontiri explained, “It was not played by women, but as time is running up, and as we are moving from analog to digital, women are starting to play it. Because nowadays, you see, they can wear trousers, but before, this one is played while you sit astride. So, women were not allowed to do so.”

“So, should I say that I’m digital?” Suzanna chided. Referencing the extreme beliefs of the danger in women playing the instrument, Suzanna told the audience with sarcasm, “Today, I’m still waiting to die. I’m still okay. Nothing wrong has happened.”

As I attended other performances and discussions, it became apparent that “women and music,” particularly female instrumentalists, would be a strong presence throughout the Festival. For example, Chinese pipa virtuoso Wu Man invited an all-female ensemble to perform at her evening concert, “Crossroads Asia: Wu Man and Friends,” and the Kenya program featured “Divas Night: Homage to Kenyan Women in Music.”

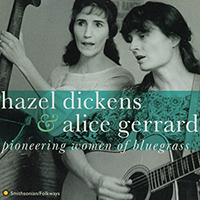

That being said, women breaking ground in music is not a new theme to the Folklife Festival. Hazel Dickens and Alice Gerard, the beloved “Pioneering Women of Bluegrass,” performed at Folklife Festivals from the 1970s into the 2000s. Standouts in a traditionally male-dominated industry, Dickens and Gerard were the first women to front a bluegrass band, paving the way for performances like my personal favorite at this year’s Festival, the collaboration between bluegrass musician Abigail Washburn and the Dimen Dong Folk Chorus.

And while one wouldn’t immediately point out the many similarities between the American bluegrass circuit, a polyphonic Chinese folk chorus from Guizhou Province, and the string instrumentalists of western Kenya, these communities are each seeing more and more women choosing to take up male-centric performance practices.

Case in point is a Miao musician I met from Leishan County in southwestern Guizhou Province, China. A dancer and musician in the Leishan Miao Music and Dance Group, Chunhua Wu is treading the way for women to learn the lusheng, a mouth organ made of multiple bamboo pipes and thought to be a precursor to modern reed instruments like the accordion and harmonica.

I spoke with her through a translator, and she was very eager to tell me that while it’s not common, women are not necessarily discouraged from playing instruments like the lusheng—it is just traditional for them not to.

It wasn’t until China’s Communist Revolution in 1949 that there was an “equalization of the genders,” as Chunhua put it. It was in the older, ancient history that women were restricted from playing certain instruments. She explained to me that even within the household, the old societal structures were extremely firm, and most fathers and grandfathers would not teach daughters about the lusheng.

However, Chunhua was told as a child in her small, rural household to “play as you like.” It was interesting to find out that she did not learn the lusheng from the older generations in her family. She learned first from her brother, and then formally in college from a teacher through whom she inherited a different generation of lusheng tradition outside of her family’s. She told me that even though her grandfather didn’t teach her the instrument, she still feels a great connection to him.

I asked Chunhua if she thought it was important for women to play the lusheng. She answered with enthusiasm. “It’s very important,” she said, “Extremely important. It’s a Miao people’s musical instrument, so it must be learned!”

Like Chunhua, Suzanna Owiyo did not learn the nyatiti from the men in her family, even though her grandfather knew how to play it. It wasn’t until a woman from Japan came to Kenya to study Kenyan musical traditions and to learn to play the nyatiti that Suzanna decided, “If a Japanese woman can come all the way from Japan to learn our music, being a woman, then who am I not to say no?”

At the Karibuni workshop, Tabu pointed out a few differences in Suzanna’s style of playing the nyatiti by setting the instrument on her lap, as opposed to sitting astride. “I’m digital, I told you!” she exclaimed. “The best thing is to just try to find my better way of playing this instrument. That was then, this is now.

“I’m very sure that in the future someone else will play it in a different way,” she concluded with certainty.

Ontiri chimed in as well. “Already the world is changing from analog to digital,” he said. “The whole world is changing. I must change. Who am I not to change?”

KC Commander is a Georgia girl with a background in musicology and is the Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage’s new media projects assistant.