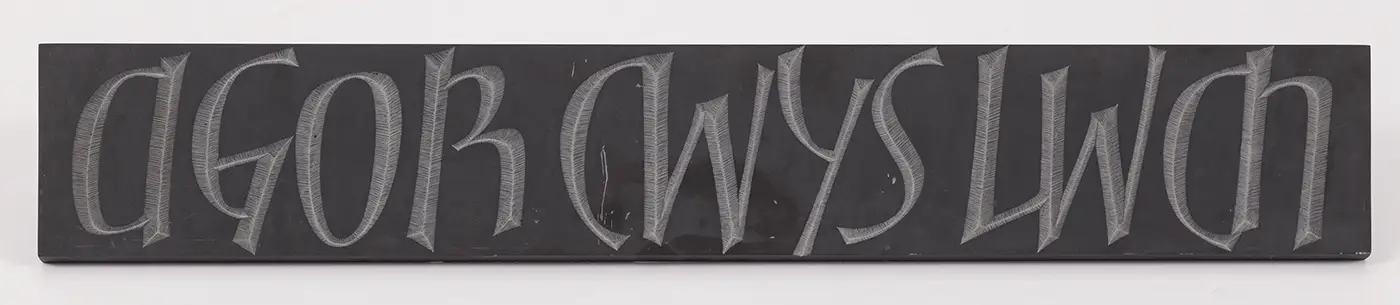

Welsh Inscription

Agor Cyws Lwch: “Opening a furrow of dust”

With these words, John Neilson created a demonstration piece to work on during the 2009 Folklife Festival. Not only could visitors watch his steady hand and keen concentration as he carved the letters but cutting them into slate gave him more to talk about: the history of slate mining in Wales, the creative process of designing letters, and his love of the Welsh language.

To “open a furrow of dust” describes what happens when letters are cut into stone, much like the farmer’s plow opens furrows of dirt in the earth. The words are also a metaphor for following your own path, which Neilson has done since pursuing a career in carving. He first worked as a teacher, then studied calligraphy in London, and finally trained with letter designer Tom Perkins in 1991.

According to the National Slate Museum, “quarrying slate is the most Welsh of Welsh industries.” By the late nineteenth century, Wales was the primary exporter of slates throughout Britain. Special skills were needed each step of the way: quarrying it out of the mountain, engineering it down steep slopes, then splitting it for use. Buildings, roofs, gravestones, and flooring were all made of slate. The carving came later, adding letters to gravestones, dates and names to buildings, words onto monuments.

Wales Smithsonian Cymru juxtaposed tradition and innovation, shining a light on the government’s sustainable development policies. Neilson’s work spans the spectrum: he uses the same tools as the Romans (hammers, mallets, chisels). Sometimes his work is put to traditional uses such as on gravestones; other times it is intentionally sculptural, laying out letters in a quilt of patterns that anticipates the daily action of light and shadow. His ability to foresee this patterning and control his cuts is masterful. By his own admission, he found his love of letters early: “I do have memories of being at primary school and looking at the lettering the teacher put up on the board, and being a bit critical about the ’A’—I was kind of a lettering nerd even then!” (Shropshire County TV)