Turkish Çini

Twenty years on, Silk Road remains a standout program

Although planning for the Silk Road program had begun several years prior to September 11, 2001, the program’s theme of “Connecting Cultures, Creating Trust” seemed prophetic at the time, tying past and present to envision a new future. Yo-Yo Ma, the visionary cellist and artistic director of the Silk Road Project, Inc., was a presenting partner that year. Through his own travels and work in different musical styles, he was captivated by the legendary trade route and how music traveled and changed along its length.

To talk to almost anyone who attended the 2002 Festival is to hear a long string of superlatives. Richard Kurin, Center director at the time, reported that “more than 400 artists, cooks, musicians, and scholars—Muslims, Christians, Hindus, Buddhists, Jews, Sikhs—from more than two dozen nations, speaking more than thirty languages” traveled to Washington that year. Over one million people attended.

Program curator Richard Kennedy concluded in that year’s annual report: “Never before has a Festival been devoted to one topic; never before has a Festival offered such research, conceptual, and logistical challenges… It has been a daunting but exhilarating effort.”

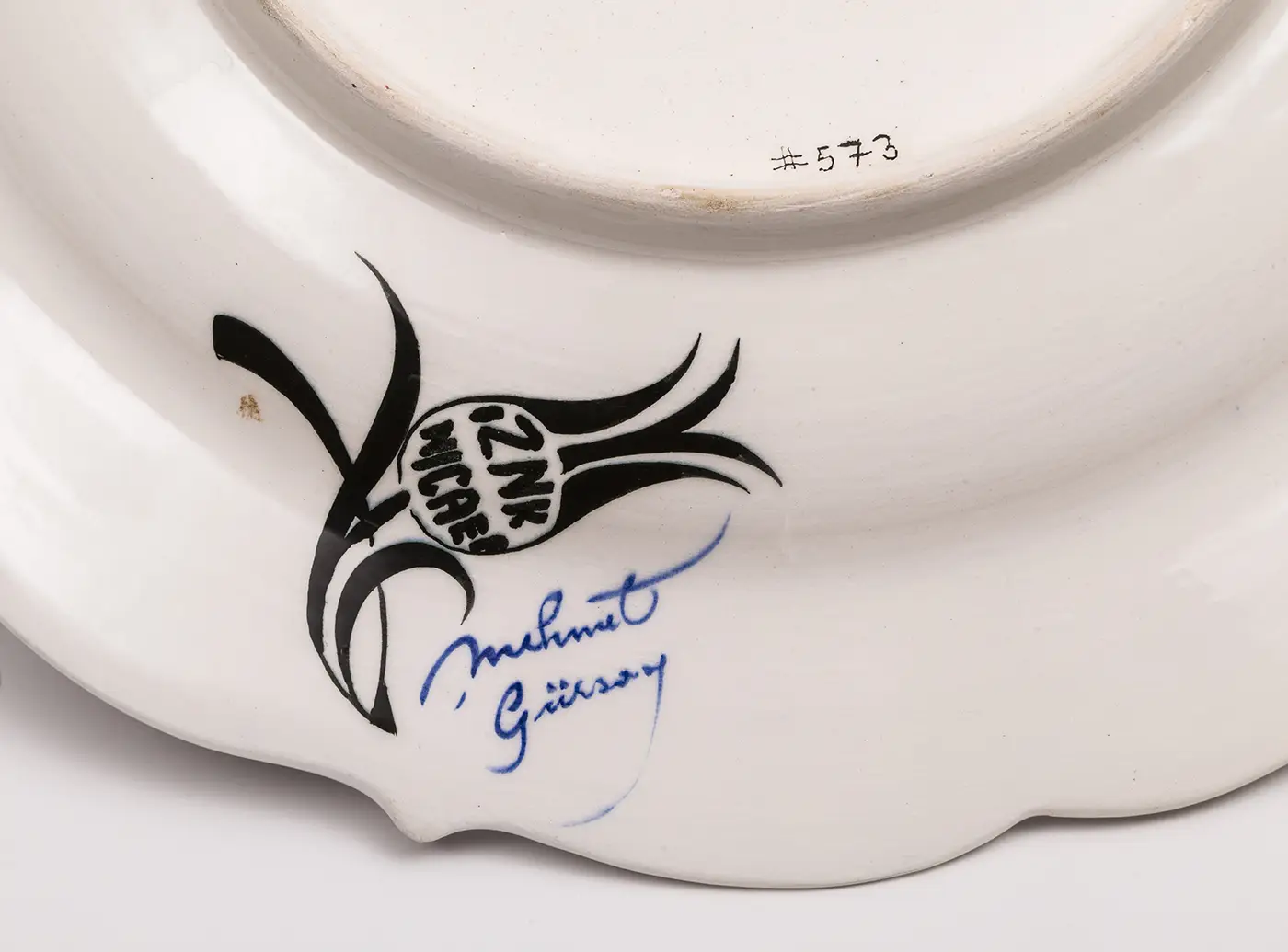

In the Ceramics Courtyard, Turkish ceramicists displayed their wares alongside Chinese, Japanese, and Bangladeshi artisans. Festival advisor Henry Glassie helped visitors understand what they were seeing in the modern Islamic çini wares:

“Turkish potters at first imitated the blue-and-white porcelain of Jingdezhen [China]. Then in a surging series of innovations, they made it their own in the sixteenth century, adding new colors, notably a luscious tomato red, and pushing the designs toward natural form and Islamic reference.”

Mehmet Gürsoy was one of four Turkish ceramicists at the Festival. Described by Glassie as a teacher and entrepreneur who “paints with delicate finesse,” he was named a UNESCO Living Human Treasure in 2009.