Mekong River Fish Traps

The greater the biodiversity of a fishery, the greater the variety of traps

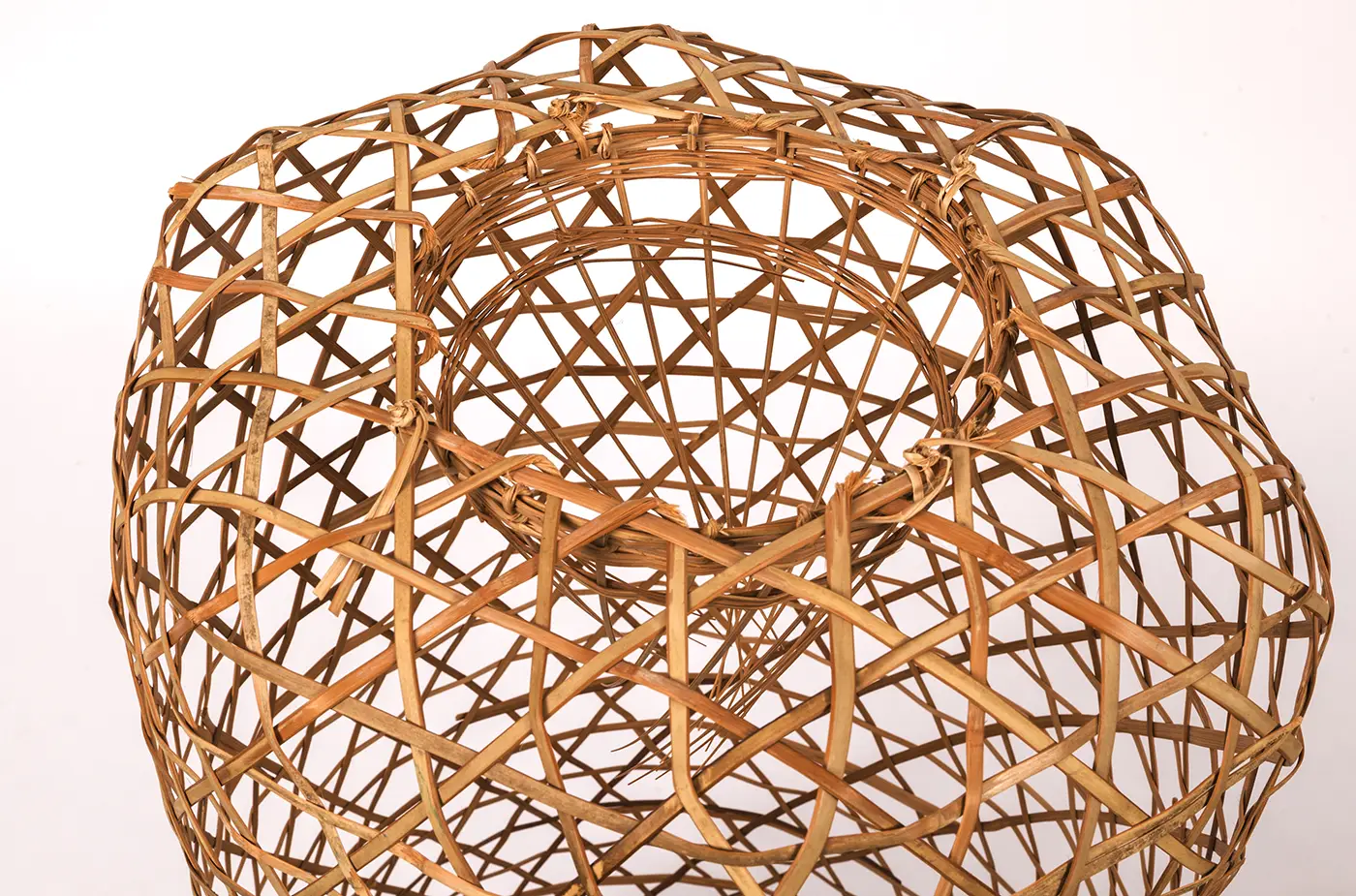

Many who visit the Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage wonder what kind of baskets these are. A closer look reveals not only distinctive exterior shapes, but interior woven funnels, and a broad range of sizes, each adapted to a specific variety of fish and the particular waterway in which it will be used (still or flowing, deep or shallow). The ingenuity behind the design of fish traps can be easily underestimated.

Seven fish trap makers from four countries—Laos, Cambodia, Vietnam, and Thailand—participated in the 2007 Folklife Festival program Mekong River: Connecting Cultures. Four years of collaborative fieldwork by Festival curators and host-country specialists resulted in detailed documentation now stored in the Center’s Ralph Rinzler Folklife Archives and Collections. These resources document the impact of development between 2004 and 2007.

The research also helped planners envision how to set up the Festival grounds. At the Festival, the participating craftspeople worked alongside one another and took turns demonstrating trap making techniques and discussing the interplay between biodiversity, natural resources, and their cultural practices. For most, making the traps provided an important supplement to their incomes, and the fish they caught enriched the family diet.

Construction of the Pak Mun Dam in Thailand began in 1991 and had a profound effect on local fisheries and fishers. “Our lives have been destroyed by the dam,” said one village fisher in an interview. Fish migration was severely disrupted, and the variety of species plummeted. The demand for certain kinds of traps declined as well. Similarly in Vietnam, a change in rice cultivation practice—which led to more annual crops but shortened the time paddies were flooded—diminished the variety of aquatic life that could thrive, leading to increased demand but for fewer styles of fish traps. The diversity of fishing tools offers a visible indicator of the diversity of the local ecosystem—and the quality of life of local residents.