For Our Family, Pierogies Are Spiritual Communion in a Dumpling

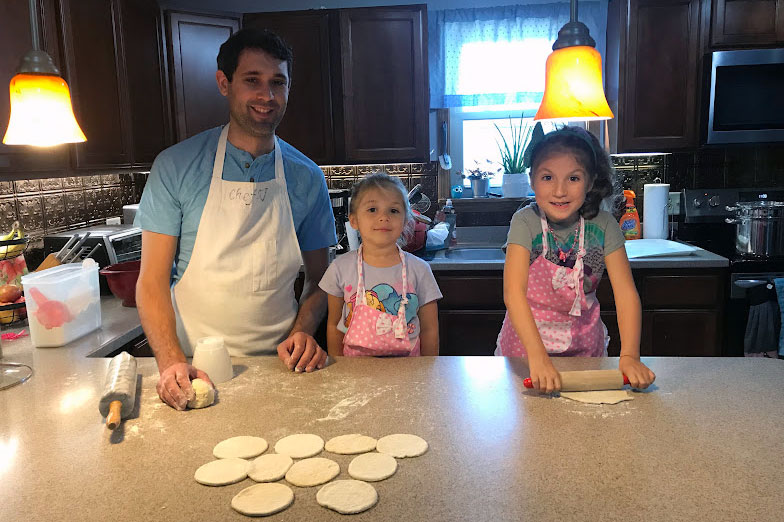

The morning I made pierogies with my two daughters: Lucy (center) and Matilda (left). Here, they are enjoying using their mini rolling pin on their own dough.

Photo by Marcie Rovan

As Grandma turned to leave her pantry, my eyes were drawn to her hands. Toughened from decades of housework, they carried containers of flour and salt. Next, she brought over a mixing bowl and a rolling pin. Wrapped in the heat of her kitchen radiator, my nose to the table, I watched her crack an egg and pour water into the flour. As she mixed, the sticky dough clung to the gold wedding band she always wore, despite having been widowed for ten years.

“Grandma, can I help you?” I said from across the table.

“Sure,” she answered, looking over to me, a small smile squeezing her cheeks.

I only have fuzzy memories of that morning, but they are warm. Although I hadn’t yet turned five, Grandma pinched off a small piece of her dough and sat it in front of me. Then, to my delight, she handed me a small wooden rolling pin, just my size. I spent the rest of the morning doing what my grandma did: rolling the dough, cutting out small circles with a plastic cup, and placing a bit of cheesy mashed potatoes in the center of the circles. My small hands weren’t yet coordinated enough to fold and seal the circles, so Grandma did that. But I got my own tiny fork to crimp the dumplings.

After a few minutes in boiling water, the pierogies were ready to eat. Grandma fished them out and sat them on the counter to cool. I peeked up and saw my kid-sized pierogies mixed in with Grandma’s. I’m sure my face beamed.

I was born and raised in Johnstown, Pennsylvania where pierogies are ubiquitous. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, millions of Eastern European immigrants arrived in the area, bringing with them foodways from their homelands. Many Slavic peoples—like Polish, Ukrainians, Czechs, and Slovaks—shared pierogies as a staple food. My family, who immigrated from current-day Slovakia, were particularly fond of them. With a dough that can be made using staple ingredients and a filling that is equally economical, they were an ideal food for Grandma and her twelve siblings during the Great Depression when money was tight.

Today, pierogies saturate the culture of Western Pennsylvania. The Pittsburgh Pirates, our regional Major League Baseball team, feature a signature “Pierogy Race” between innings where contestants dress as human-sized pierogies and race around the field. There is also the annual Pierogi Festival, where you can find savory pierogies filled with jalapeños or bacon and dessert pierogies stuffed with apricot preserves or prune jam.

In this secular space, pierogies represent a region, its ethnic people, and memories of an immigrant past. But these simple dumplings are also symbols of sacredness for many, my family included. As Catholics, we observe the Church’s religious holy days, and those religious beliefs are reflected in our homes, guiding us in the foods we prepare.

Growing up, I watched Grandma keep close to these Slovak Catholic traditions. On Christmas Eve, she prepared a feast of traditional Slovak soups and breads. At Easter, she observed the Blessing of Easter Baskets, when she took some food prepared for Easter (like ham, butter, cheese, eggs, and bread) to the church hall to be blessed by the priest. We all shared the cold food for lunch on Easter Sunday.

Within all of this, pierogies were a constant food. Never reserved for special occasions, pierogies were always in the freezer. When cousins from Arizona visited one summer, Grandma knew they would want pierogies. But she didn’t anticipate how they would want them prepared: pan-fried, crispy, in butter. “More fried pierogies!” they yelled from the dining room, and Grandma couldn’t fry them fast enough.

A few years later, as my fiancée, Marcie, and I planned our wedding, Grandma offered her traditions to unite our families. My family lived far from the venue, which complicated our plans for a large wedding that everyone could attend. Determined to make it work, Marcie and I turned to Grandma. She helped us make pierogies to sell to everyone we knew, and the money we raised paid for a charter bus.

If religion is focused first on the people who practice it, rather than on dogma, then foods that link us in community are spiritual symbols. The folklorist Leonard Norman Primiano wrote that “vernacular religion … highlights the power of the individual and communities of individuals to create and re-create their own religion.” For me and my family, our food traditions enact a type of vernacular religious tradition in which we commune with other family members, no matter how far apart, alive or departed. Pierogies remind us not only of our distant ancestors, who may have toiled in the fields and farms of Slovakia, but also of our closer relatives, whose presence enriches our lives.

The memory of making my own small pierogies as a youngster remains one of the fondest that I have with my grandma and one that I often think back to. For almost thirty years, I believed it illustrated her commitment to sharing her Slovak culture.

But a few months ago, I was forced to reconsider what exactly motivated my Grandma on that winter morning when I was five. It was another chilly day when I ventured to make a batch of pierogies with my own two young daughters, who had just turned four and seven. Raising them in Southwestern Ohio, where we had moved for work, I knew they weren’t going to encounter pierogies on a regular basis. They were ready—in my mind—to share in the food traditions that Grandma had passed on to me.

But before we even started, I could sense disaster. It was one of those restless afternoons full of tears and flying toys when, if I didn’t keep a close eye on the kids, flour would end up on the ceiling.

I decided to power through. Yet as I prepared the dough, tiny voices called up at me: “Dad, how much flour are you adding?” “Dad, why are you mixing an egg in there?” “Dad, can I help?” “Dad, I really want to do that.” The cacophony of requests was overwhelming, never mind that both girls were just getting over winter colds. I reconsidered. I didn’t necessarily want their tiny, germ-ridden mitts in my dough.

And then, as the mixture clung to my own wedding band, I remembered my grandma, and inspiration struck. “Sure, you can help,” I told them. “Here’s a little piece of dough and a rolling pin.” They dutifully rolled out their doughs as best as they could, cut circles with their own small plastic cups, then after I sealed the dumplings, crimped them with their small forks. They weren’t perfect and almost made me laugh. They were lumpy, uneven, and many were bound to break open as they cooked. But soon the pierogies went into their own pot of boiling water. A few minutes later, both girls’ faces shone with pride at the food they had created, mini versions of what I was pulling out of the larger pot.

I realized at that moment that that’s how these traditions are passed on: little hands need to be busy. Over time, they’ll develop reverence for the craft, infusing the tradition with their own joyful memories.

For us, pierogies are sacred but never solemn.

At the 2023 Smithsonian Folklife Festival, Aaron Rovan will lead pierogi workshops in the Creative Encounters program’s Kitchen Theology tent. Registration for the workshops is currently full, but a limited number of walk-ins can join, and other visitors can watch the preparation. Get his pierogi recipe.

Aaron Rovan is a folklorist and former intern at the Smithsonian Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage. Currently he is a program officer at Ohio Humanities, where he is excited to continually hear others’ stories of their own cultural heritages.