Turkish Çini

A stand-out female artist in a male-dominated field

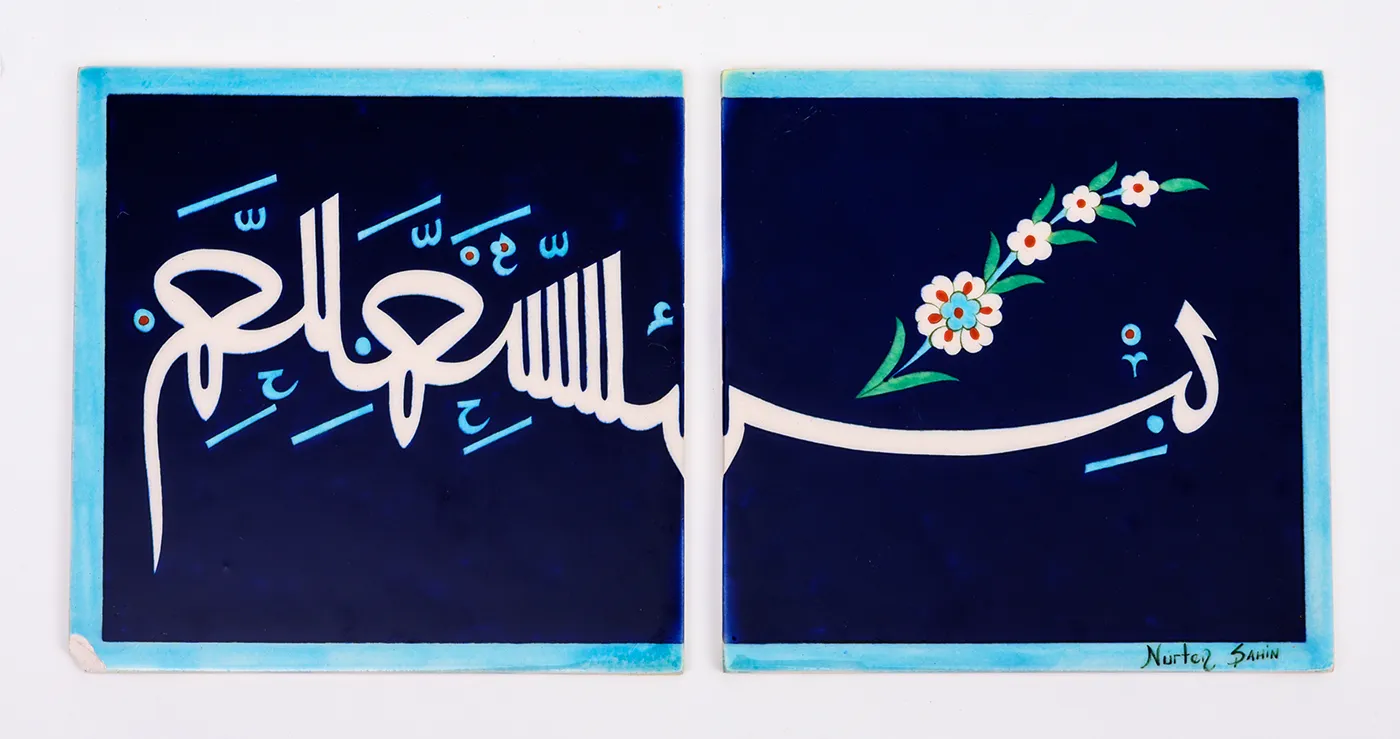

Nurten Şahin’s painted plates and tiles were on view in the Ceramics Courtyard, where she shared space with her husband, Ahmet Hürriyet Şahin, and fellow çini artist Mehmet Gürsoy—all three of them from Kütahya, Türkiye. In 2002, she was one of few female designers working within the tradition.

In 1986, folklorist Henry Glassie wrote about Turkish ceramics for the Cultural Conservation Festival program, creating a framework for the Silk Road-themed Festival in 2002. In “A Lesson from Turkish Ceramics,” he refers to the senior Ahmet Şahin (grandfather to Nurten’s husband) as Kütahya’s “most revered” çini designer. He details the production process and notes the creativity and skill required to develop lasting designs.

In the 2002 Silk Road program book, Glassie and Pravina Shukla expand on the role of women in the production cycle of çini plates and tiles, twenty-five years later:

“Men mix seven elements to make a composite white substance—they call it mud—that is shaped, slipped, and fired. Women… draw the designs, filing them with vibrant color before the ware is glazed and fired again. They make tiles to revet (reinforce) the walls of new mosques. They make plates, domestic in scale and association, that do at home what tiles do in the mosque, bringing shine and color and religious significance to the walls.”

Glassie’s work inspired a 2010 research project by Rija Qureshi, a 2010 Katzenberger art history intern at the Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage, which she turned into an online exhibition: Modern Islamic Ceramics: Çini Traditions from Turkey.