Korean Onggi

Specialized pottery for fermenting and preserving Korean foods

For centuries, onggi were essential to preparing and storing the core staples of the Korean diet: soybean and red chili paste, spicy kimchi, and more. The low-fired earthenware has a distinctive porosity that allows oxygen to enter without letting liquids evaporate, aiding the fermentation process required for these foods and condiments. With that trait, onggi has persisted for hundreds of years, even after the introduction of commercial wares and refrigeration.

The onggi making industry was little known and poorly documented outside of Korea until the early 1970s. On his first trip to Korea in 1971, Folklife Festival director Ralph Rinzler was captivated by the large, lidded jars he saw clustered outside village homes. He returned the next year to do more research and again a decade later with anthropologist Robert Sayers as they prepared for the 1982 Korea-USA Centennial program. In the ten years since his first visit, Rinzler found that Korea had modernized and many of the rural pottery sites were consolidated or gone altogether. He also noted a sharp decline in apprentices learning the trade, even as collectors were beginning to purchase the older onggi.

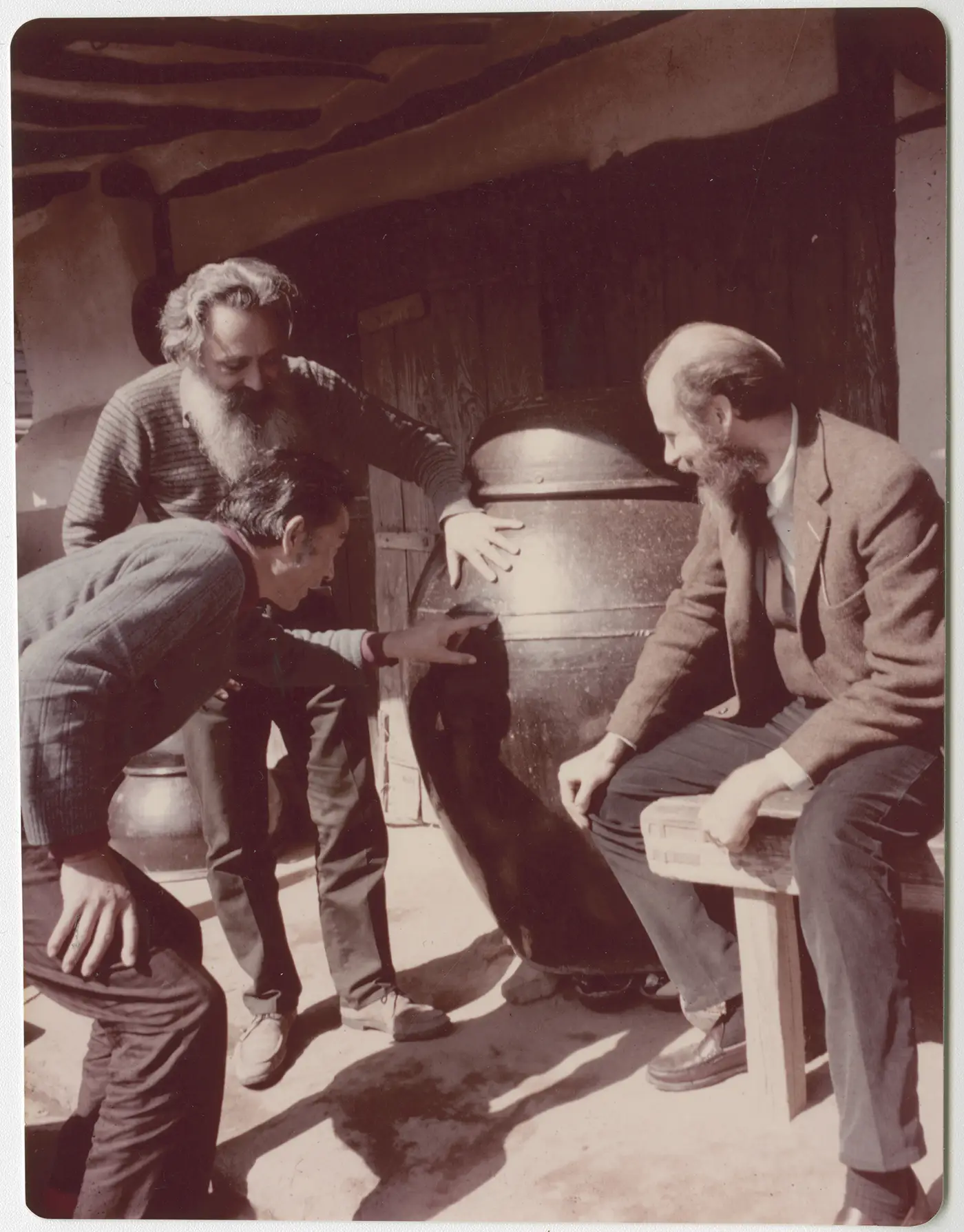

During that trip, Rinzler and Sayers invited Mr. Shim Sang-un to demonstrate at the Festival. Having started as a potter at seventeen, he now owned the Ch’owŏl Pottery Factory in Kyŏnggi Province and brought an array of finished pots to display adjacent to his work area (above).

Today, there are a handful of onggi on display in the Center’s lobby case. Most came from the Festival Marketplace, but the larger pot at top left holds a slightly different story. In 2018 Robert Sayers visited the Archives and confirmed that Shim Sang-un made pot while at the Festival. He drew our attention to its “strange glaze,” chucking as he recalled that Rinzler arranged to have it fired at Jugtown Pottery outside Seagrove, North Carolina. “It was the closest approximation the Jugtown people could come up with—either Japanese Tenmoku or Albany slip.” When fired, it melted nearly clear around the middle and took on a chocolate tone over the rest of its body—subtly distinct from the other onggi around it.