Ballad Collecting Across the Ozarks: An Introduction to Max Hunter

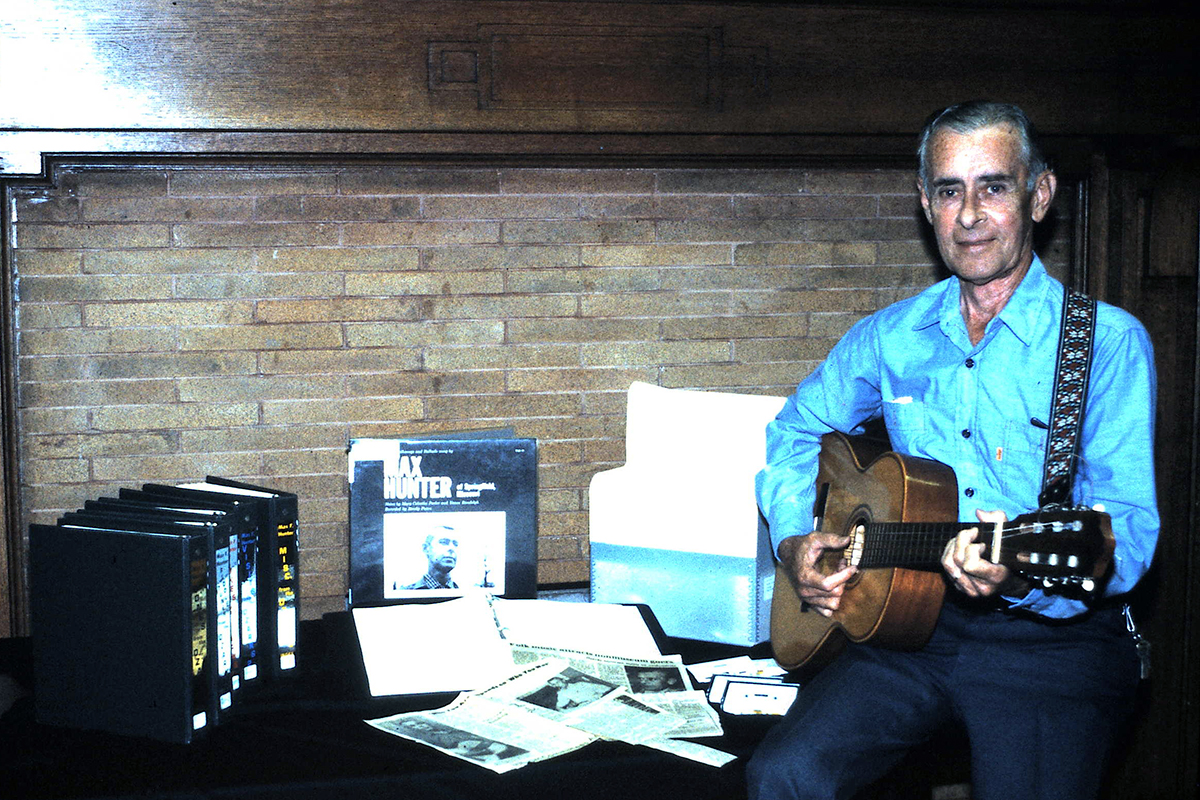

Max Hunter with his bound song volumes, circa 1976.

Photo courtesy of the Springfield-Green County Library

My first introduction to the Ozarks was the Max Hunter Folk Song Collection. As a ballad seeker myself, I stayed up way past midnight one night skipping from one song to the next and found myself caught up in the astounding variety of voices and materials. I would spend nearly a decade immersing myself in the collection, and I’ve yet to hear every song. Early on in my Hunter discovery, I became curious not only about the singers but about the life of the collector himself, a refrigeration technology salesman and father of four from Springfield, Missouri.

Born in 1921 in Ozark, Missouri, and active in song chasing from 1956 to 1976, Max Hunter spent twenty years recording nearly 1,600 traditional songs from more than 200 singers. He grew up in a house filled with old songs. His mother, Ethyl Rose, sang a lot of old ballads and parlor songs, and family and friends enjoyed singing together on road trips. Still, it would be years before he realized the cultural importance and the fragility of the oral tradition he had once taken for granted.

Hunter graduated from high school, got married to high-school sweetheart Virginia Mercer on Christmas Day, and went straight to work. Luckily, for the survival of Ozark balladry, he made a habit of recording songs during his repeated sales loop through the Ozarks. My singing friend Martha Grace drew a “folk” map which gives some idea of both his travels and the sources he would return to over and over again.

“Some of the places I have been to collect were almost at the end of the proverbial ‘no-where,’” Hunter once wrote. “Down in hollows that were two miles down hill, over glorified wagon trails, country roadside tavern[s], on top of small mountains that overlooked large rive[r]s and wide valleys, into homes where the very barest of necessities were visible, into the finest homes in the community, into farm homes…service stations, hotel lobbies…sheriffs offices…anywhere I could find someone with a song.”

Hunter understood that his fellow Ozarkers did not think of themselves as singers or performers—they simply sang in connection with family, church, and community. People remembered what their songs were about and from whom they had learned them, but they rarely recalled the titles.

He also understood how much the songs meant to their holders, and so he spent twenty years getting to know his sources. This often took the form of helping them out with farm chores. The heavy Web Core reel-to-reel tape recorder only came out at the end of the day or in the evening. He had the salesman’s knack for putting people at ease, and songsters rarely refused him.

Here are just a few samples of some of my favorite recordings from the Max Hunter Folk Song Collection, housed at Missouri State University:

All these songs were captured in the Ozarks exactly as they were sung, because Max Hunter’s number one rule was never to alter a song. The lyrics he meticulously wrote down—sometimes with the help of family members—don’t always makes sense, nor do their titles. But this is how Hunter wanted it: the real deal, the material as it was delivered.

As Hunter’s collecting days drew to a close, he chose to bequeath his tapes and related materials to the Springfield Greene County Library, where patrons had full access to the collection. I was at the library recently to present my first published book, Ballad Hunting with Max Hunter: Stories of an Ozark Folksong Collector, and I am happy to report that, a full twenty-four years after Hunter’s passing in 1999, interest in his collection is alive and well. Over fifty people showed up, including members of the Hunter family who generously shared what it meant to be the children of a ballad-chasing father, and, as they collectively expressed it, “a fine fella.” I was joined by farmer, storyteller, and longtime songster Judy Domeny Bowen, as well as song scholar and performer Julie Henigan, both of whom knew Hunter and sang for him at the Ozark festivals he helped organize.

There were also younger audience members at the Springfield library who asked questions about Hunter’s “avocation” and shared observations regarding the authenticity of the ballads. In short, the songs Hunter captured evoke an era of Ozarks music that still resonates today.

Sarah Jane Nelson is a writer, educator, and musical performer based in New England. She is the author of numerous articles on environmental conservation and more recently on song preservation and the preservation of musical folklore. Ballad Hunting with Max Hunter was published in January 2023 as part of the University of Illinois Press’s Music in America Series.