How Musicians Use Native Languages to Revitalize Their Cultures

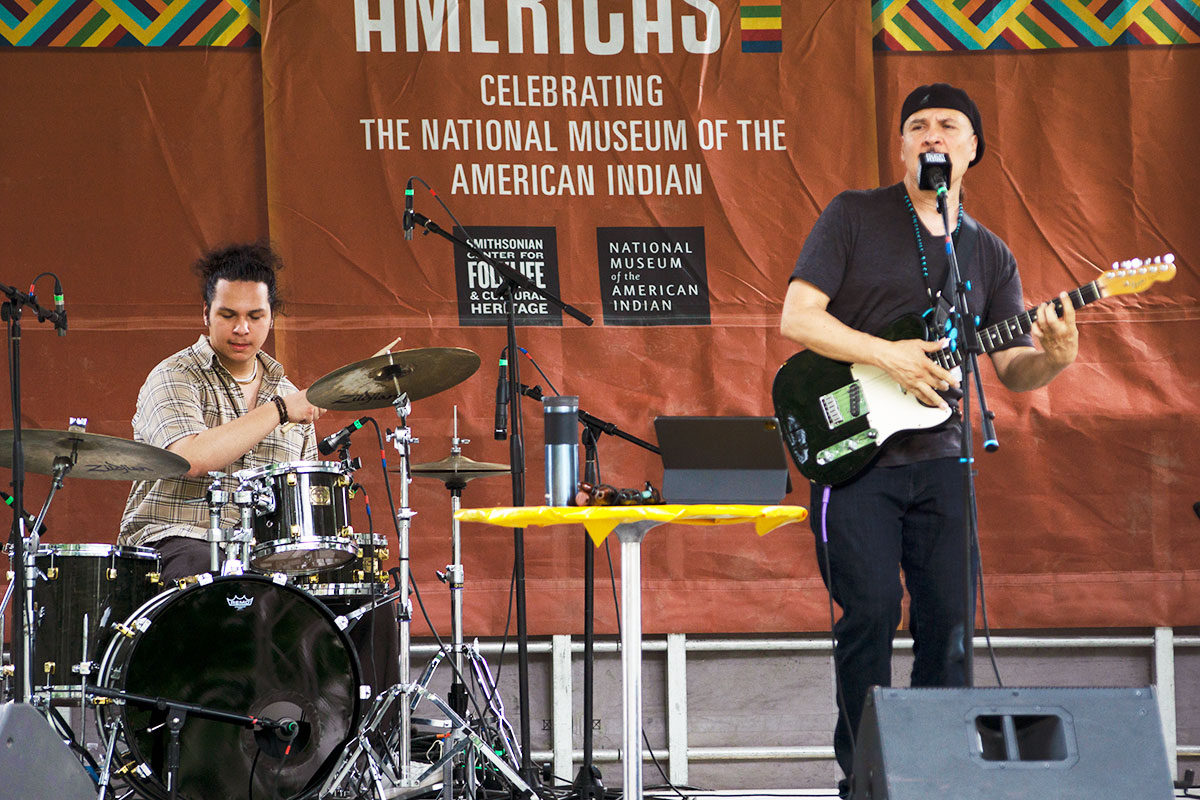

Quintin (left) and Wade Fernandez perform on the Four Directions Stage at the 2024 Smithsonian Folklife Festival.

Photo by Carys Owen, Ralph Rinzler Folklife Archives

At the 2024 Smithsonian Folklife Festival, visitors may not have been surprised to hear musicians striking drums and playing resonant traditional flutes. What may have been surprising about the Indigenous Voices of the Americas program, though, was hearing rap music and bluesy guitar ring out from the Four Directions Stage.

Many Indigenous musicians are shaking up the modern musical landscape. By combining their Native languages with contemporary sounds, these artists revitalize and reassert the importance of their cultures in the modern world.

As clear waters flow and tears come and go

We fly our own ways

Take these seeds and sow; let them nourish your souls

And plant them everywhere you go

Singer-songwriter Wade Fernandez, from the Menominee Indian Tribe of Wisconsin, plays both guitar and traditional flute in his English- and Menominee-language songs—like this one, “Sawaenemiyah.” With these instruments, along with drumming from his son Quintin, he creates melodies inspired by his Menominee, European, Mexican, and other Indigenous ancestry. His sound represents this combination of cultures in many ways, making it at the same time both traditionally Native and new.

Today, Native American culture is often relegated to the margins of history textbooks, if not completely erased. The Menominee nation has long struggled with such a fate. In 1883, with the opening of St. Joseph’s Indian Industrial School, the tribe fell victim to the United States’ efforts to forcibly assimilate Native Americans. The government established hundreds of Native American boarding schools around the country which separated Indigenous children from their families, banned them from speaking their Native languages or wearing Native clothing, and taught them a version of history which either villainized or erased their history. With children disconnected from their traditions and languages, Indigenous cultures suffered.

St. Joseph’s closed in 1952, but its effects still linger. Recently, with the creation of the Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative in 2021, the American government has begun efforts to repair the cultural damage enacted by its Native American boarding schools. Healing from such complex generational trauma will take time and effort.

The Menominee nation contended not only with the cultural decay enforced by boarding schools, but also with outright erasure when their federal recognition was revoked in the 1950s. Despite these challenges, the tribe has remained committed to asserting its identity. The Menominee people fought to win back the tribe’s federal recognition and, in 1973, achieved it with the Menominee Restoration Act.

In his own way, Fernandez asserts the cultural relevance and importance of his tribe through his Menominee lyrics. He was eager to share the tribe’s efforts toward language revitalization, including an immersion school for children and a grassroots movement called Menomini yoU. He says preserving the language is important to him because “it contains our way of thinking as Menominee people—it contains our stories.”

He believes that the world thrives through diversity, and by using his Native language in his music, Fernandez preserves cultural diversity for his contemporary audience.

“It’s like the trees—if they were all just pine trees everywhere, it would be a boring forest, and you’d have no apples, no pears, no lemons, no walnuts, all these different things,” he explained. “It’s the same with cultures. We need all the beauty of all these different cultures, and the language is a big part that contains the wisdom of the culture.”

For Mapuche musician Ketrafe, using his Native language of Mapuzungun is also about revitalization. Although he reached a global audience through the Folklife Festival—with performances alongisde Mapuche rapper Waikil on the National Mall, the Kennedy Center, and Reagon Washington National Airport—the artist is chiefly concerned with reaching the youth within his own community. He believes that only by revitalizing Mapuche culture, art, and teachings, “can we ensure its existence, creating new speakers of the culture.”

The Mapuche people have faced a long history of discrimination at the hands of the Chilean government. This discrimination hit a crescendo under the dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet, who took power from President Salvador Allende in a military coup in 1973. During his authoritarian regime, which ruled until 1990, Pinochet tried to erase Indigenous identities in Chile, declaring that “there are no Indigenous people, only Chileans.”

His government took land from the Indigenous population, passed a still-controversial anti-terrorism law that unfairly targets the Mapuche people, and drew up a constitution that remains the only one in Latin America that does not recognize its Indigenous population. State schools punished children who spoke their Native languages and forced them to speak Spanish, which was seen as more proper and respectable. Many Mapuche stopped using Mapuzungun due to fear of being targeted by Pinochet’s government. As a result, though there are over 1.5 million Mapuche people in Chile (according to the last census), only a quarter speak Mapuzungun.

Ketrafe does not let this discourage him. “Today, we are fighting to heal that colonial wound,” he says.

Ketrafe heals through his music: “It is not only an exercise in memory, but also in resistance.” With his blend of Mapuzungun lyrics and contemporary sounds, Ketrafe repairs some of the damage that past and ongoing oppression has done to his nation, revitalizing the culture for the younger generation.

“Maybe we are not in the music industry, but we are in the ears of our own Indigenous people of the world. And that, to me, is beautiful.”

He seeks to reach his own nation, but there is also value in seeking a wider audience, especially when that audience often misunderstands and misrepresents your culture.

The world today tends to think of the Maya people in historical terms, an empire from an ancient era. If you Google the term “Maya culture,” you will see many articles explaining who the Maya were, what their culture was like. In her music, Kaqchikel Maya musician Sara Curruchich revises these statements; she makes it clear that the Maya are—not were—a strong and resilient people.

As one of the first singers to expose international audiences to her Native language of Kaqchikel, Curruchich is a strong cultural ambassador for her heritage. She composes songs in both Kaqchikel and Spanish, putting these languages to mixes of folk, rock, and traditional Maya tunes. These sounds, combined with topics that are at the same time personal and universal, form music that highlights the complexity of the modern Indigenous identity.

Curruchich engages with contemporary conversations on identity not only through music but also through activism. She is an ambassador for the UN’s HeForShe movement, a global effort that promotes gender equality. Additionally, during the meet and greet after her featured concert at the Folklife Festival, she urged visitors to scan a QR code which connected them to a GoFundMe that she created on behalf of Fondo Semillas, a feminist fund in Mexico that combats oppression against the country’s cis women, trans women, girls, and intersex individuals. As part of their efforts, the fund works with collectives in states with high Indigenous populations to address the unique challenges of the women in those areas.

At the bottom of the GoFundMe page, Curruchich includes lyrics from her song “Mujer Indígena” to state, “Like our grandmothers with their warrior soul, and like the earth with our brown skin, we are Indigenous women, granddaughters of the moon. This is our strength!” Just as she does in her music, she asserts her place as an Indigenous woman both in the world and in modern discourse about gender and equality.

This, ultimately, is the importance of using Indigenous languages in contemporary music. These voices assert that Native cultures, as well as Native people, are still relevant despite the oppression and erasure they have faced. The mainstream audience may not understand their languages, but their voices are nonetheless powerful as preservers, protectors, and promoters of their cultures. As Curruchich affirms in her song “Abriendo la Voz”:

I will open my voice

Sing a song

To the wind, to your heart

To the waters, fire, and sun

To the souls that live in the rivers

and the sea

Voices, all the voices,

To the spirit of the forest

Voices to wounds, memory, history

Songs to the cornfield, fireflies, and sowing

Songs to the rain and the beating

Songs by the voices of the people

Devon Szczepkowicz is a program intern for Indigenous Voices of the Americas at the Smithsonian Folklife Festival. She is a rising sophomore majoring in history at Gettysburg College.