Back to Base: Fugazi & the D.C. Punk Zine Scene

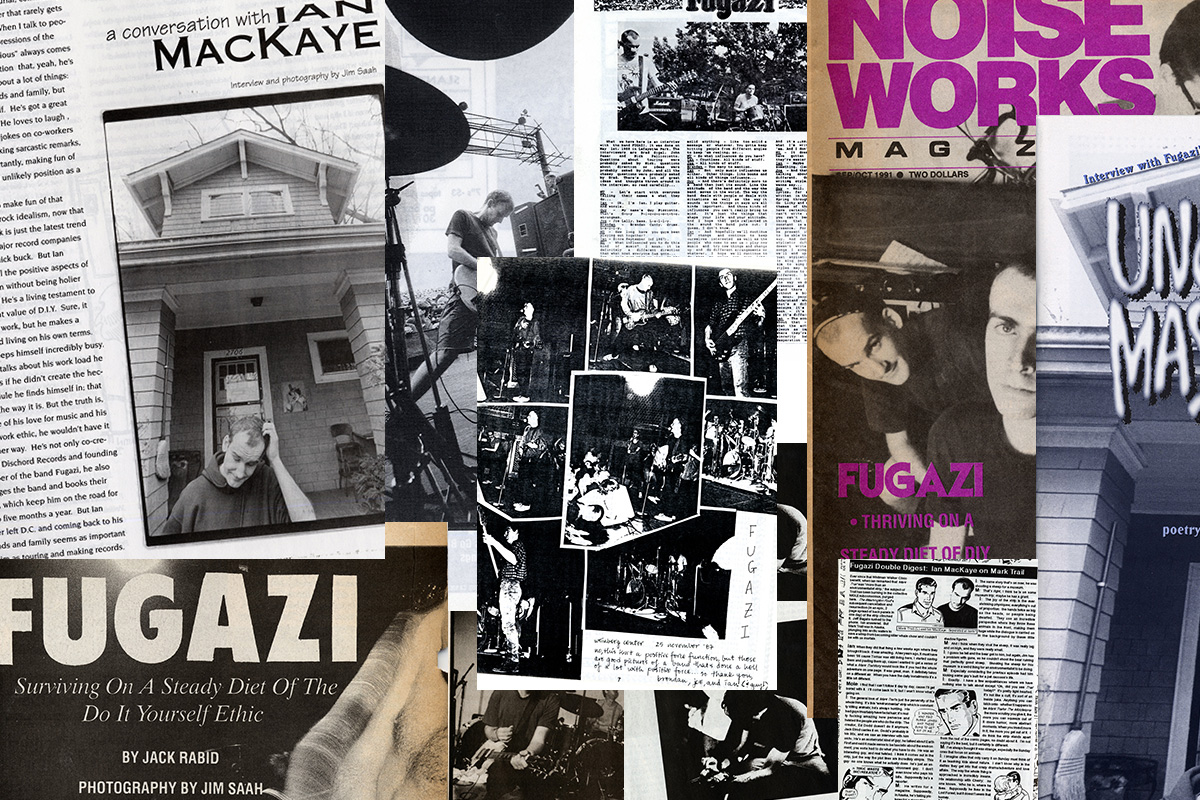

Collection of punk fanzines featuring D.C. band Fugazi. Photo by John Davis

When Guy Picciotto from the D.C. punk band Fugazi was asked in 1993 why the band declined interview requests from mainstream music publications like Rolling Stone and Spin, he explained: “’Cause we don’t like those magazines! I mean, we’d rather do fanzines.”

Fanzines are independent, often highly personal, small-run publications created by fans of a specific subject: everything from science fiction to celebrities to local punk rock scenes. Indeed, fanzines boasted a level of access to Fugazi—a fiercely independent and enormously popular group—that larger music magazines could only envy.

The members of Fugazi—guitarist/vocalist Picciotto, drummer Brendan Canty, bassist/vocalist Joe Lally, and guitarist/vocalist Ian MacKaye—willingly sat for interviews with hundreds of fanzines from the band’s inception in 1987 until it went on an indefinite hiatus in early 2003. Several of those fanzines—Mole, Uno Mas, Action Teen, and Nomadic Underground, among others—came out of the D.C. punk community and provided the band with a forum to freely express and explore many of the ideas and practices at the core of the band’s existence.

Fanzine editors distributed their publications throughout the D.C. area using a network of independent record stores, merchandise tables at concerts, and word-of-mouth communication among fans. Creators employed a variety of aesthetics within the pages of their zines, but whether it was the crudely hand-lettered, cut-and-paste look of early issues of the 1980s title WDC Period or the slick, professional approach of a 1990s publication like Who Cares, the idea was the same: who better to write about this music scene than its participants?

Fanzines have been an important part of the punk scene in D.C. since it first emerged in the second half of the 1970s. Early D.C. punk zines like Vintage Violence, Descenes, and The Infiltrator provided otherwise scarce coverage of pioneering bands like The Slickee Boys and Bad Brains, paving the way for an explosion of fanzines that occurred as the scene grew throughout the 1980s and ’90s. Led by publications like Truly Needy, Greed, and Thrillseeker, the 1980s punk fanzine scene in D.C. was among the first to cover the local bands that helped define the city’s sound, like the epochal Minor Threat or the highly influential Rites of Spring.

The tradition continued in the 1990s, when zines like Riot Grrrl, Scorpion, Not Even, and Fake pushed D.C. punk into new places, challenging norms within the subculture and helping to spread the word on the exciting new ideas and sounds that continued to come from the community. Although the growth of the internet greatly reduced the number of print fanzines as the twenty-first century unfolded, some titles still publish today, like Shining Life and Demystification.

The foundation of D.C. punk fanzines was well established by the time Fugazi appeared in the late 1980s, enabling the band to effectively reach fans everywhere, while still circumventing traditional publicity methods and supporting the independent press. Although some mainstream music publications referred to Fugazi as a band that refused to do interviews, they were simply wrong.

“We're not trying to hide ourselves,” Picciotto explained. “If people want access to the information or want access to the band, it’s readily available. The point is just not to overhype it or overplay it.”

Thanks to Fugazi’s relationship with its hometown fanzines—along with countless other zines around the world—there was often no better source for that information.

John Davis is the Performing Arts Metadata Archivist at the University of Maryland. He is currently writing a history of D.C. punk fanzines for Georgetown University Press, and he co-curated the Visualizing Fugazi exhibition now on view at Lost Origins Gallery in Washington, D.C.

In 2019 we are celebrating the Smithsonian Year of Music, with 365 days of performances, exhibitions, and other music-related programming around the institution. Learn more at music.si.edu.