Family Photos of an Adopted Homeland: Personal Archives in the UAE

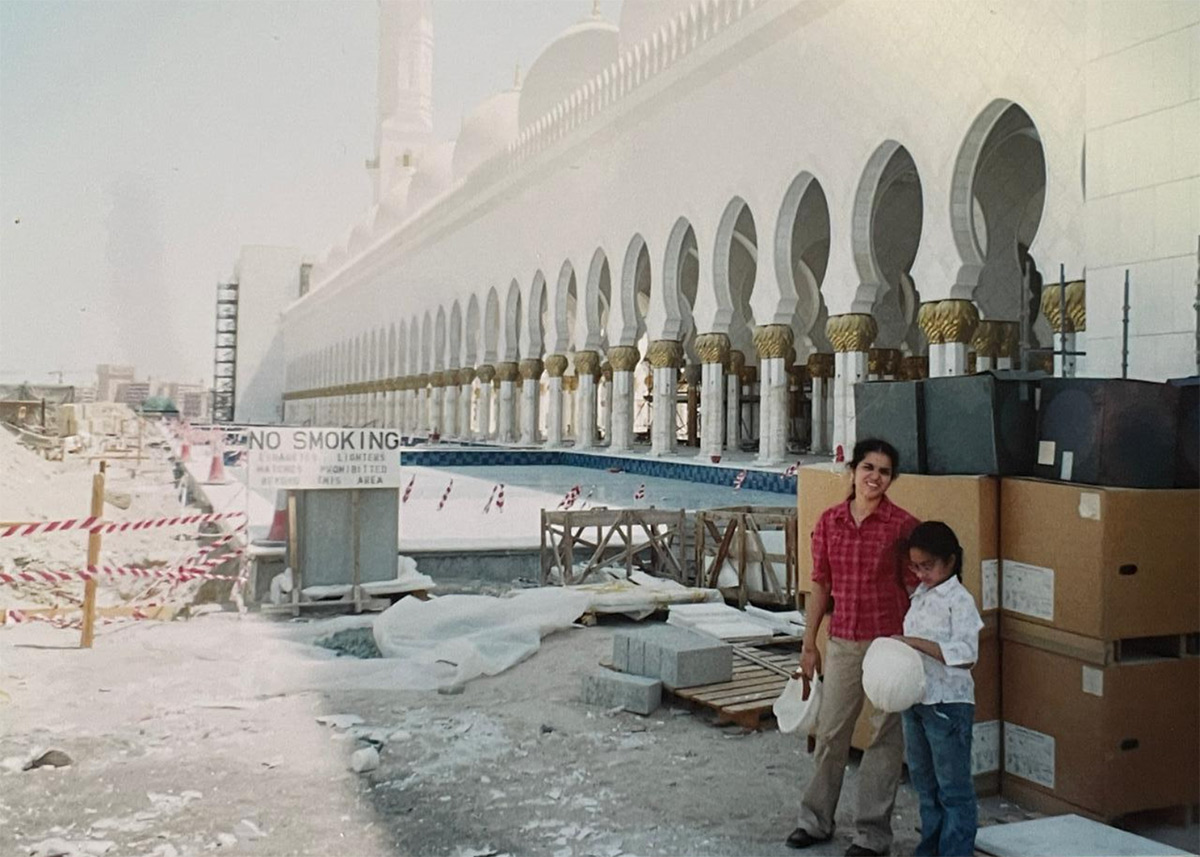

Aathma Nirmala Dious and her mother at a construction site by the Sheikh Zayed Grand Mosque in Abu Dhabi, c. 2006-07.

Photo courtesy of Aathma Nirmala Dious

Many homes in the United Arab Emirates contain albums filled with photographs of family excursions and time-marking portraits. Glossy, gelatin silver or worn printed photographs reveal unofficial histories of family life in the United Arab Emirates. Family photographs—of Emirati nationals and expatriate residents—can be read as grassroots records rather than simply sentimental objects. Family photographs bring a diversity of experience and perspective to the official photographic archive of the young nation celebrating its fifty years.

As a student at New York University Abu Dhabi studying photography, I turned to my peers to find out how people in the UAE look back on its history. With students hailing from over 120 nations, NYUAD also hosts Emirati and UAE residents on campus, some of whom were willing to share their photographs with me. I spoke to students whose parents come from Kerala, India, but who were born and raised in the UAE. I spoke to an Emirati alumna who creates visual art with her family photography in response to childhood amnesia. And I spoke to a student whose family has come to, left, and returned to the UAE three times since the 1980s.

Such dynamic nomadism constitutes the essence of the Emirates: as of 2014, the country’s population is 88.4 percent expatriate. While many UAE residents have a temporary official residency, during their sometimes lifelong stays in the Emirates, these communities create alternative forms of belonging, which may not appear in “official” accounts. As both a document and an emotional cue, photography offers a way of looking at community in the UAE, where space is constantly changing.

These communities have attachments to the UAE and its social spaces and in turn reveal a collective memory using photography. With this, expatriate families are integral to developing a memory space in the UAE, a memory that is no longer apart from spatial existence but attached to it through recollection and the imagination. To understand these claims to national memory, I spoke with students about photographs they selected from their family archives—images that illustrate change and collective memories, that are valuable for not only understanding the history of the UAE but linkages to other countries as well.

Sreerag Jyothish: The Story Isn’t Just Fable

Expatriates from the Indian state of Kerala initiated their immigration to the Gulf states in the early 1940s. Sreerag Jyothish’s grandfather, also hailing from Kerala, made the arduous journey to the Gulf sometime in the 1960s or ’70s during the oil boom in the UAE.

Following his arrival, the family history is blurred. By piecing together family records and oral histories, Sree’s family has determined that their grandfather was in the army and had moved around between emirates. The crackling and damage on the group portrait perhaps accentuate the fogginess of family record-keeping. Even though the story behind this particular moment is ambiguous, this photo depicts Sree’s relatives in a significant place, the Abu Dhabi airport, testifying to their journeys through the Gulf.

Does photography verify our memories or confuse them further? Sree explained the role such records and family paraphernalia played in his fable-like understanding of his grandfather’s life: “Photography becomes this vantage point to look back. Because when I saw my grandad before, it was all stories, right? Being like, ‘oh, my grandpa worked for the army.’ I was like, ‘that could be true.’” For Sree, finding his grandfather’s military uniform and studio portraits of him in uniform affirmed the facts of his family’s narrative of belonging in the UAE.

In Sree’s third image, we are transported to Dubai in the late ’90s. In his father’s arms, Sree is adorned with the white fabric typical of an infant. His parents are in Indian dress, on the way to a Hindu temple. In a country whose spatial landscape is constantly altered and recreated, it is rare for a place in old family photos to still exist.

“For me, this place has always remained important,” Sree said. “The temple has changed a lot even since when I was a child.”

Despite the changes it underwent, the temple becomes a place of nostalgic attachment through tradition and feeling rather than a constant in physical space. In the UAE, photography plays an important role in documenting how places disappear during an era of rapid growth.

“When I was looking at these photos, it’s more apparent how a lot of places are really just gone,” Sree reflects. “It’s hard to really look at a place and be like, ‘oh, that’s where I grew up.’”

In Sree’s case, his family record-keeping has become a means of creating nostalgic belonging. Photography lets us hold onto those places that may disappear within ten years. When we cannot go back to a place, we search for it in the archives.

Harry Creber: Charades

What if our family records do not accurately reflect our family histories? Harry Creber’s father migrated to the UAE in 1985 to serve as a teacher at a private school in Dubai. Following career complications, his father departed and returned in 2008 to again work as a teacher at a supposedly renowned private school. Like many, his family came to the Emirates for financial and economic benefits as well as a free private education for their child.

Despite the promises of a stable life, Harry’s family faced tremendous difficulties during that period due to the worldwide recession and complications with mismanagement at the school. Harry’s memories of this time are bittersweet. Above, a studio portrait shows Harry posed in the school uniform with an ambiguous half-smile.

“I enjoyed my time there, I felt happy. But I am aware now that it was kind of fake. A lot of it was. Especially that photo. I think that photo sums it up. This was meant to be some sort of charade of some fancy private British school that never happened.”

The other students I spoke to expressed similar sentiments about studio portraiture in general. They favored the more candid, intimate shots of their family members celebrating birthdays over the formal portraits their parents might display in their living rooms. Harry’s family did not take any photos together in Dubai, a reflection of the turmoil they faced. With gaps in his family’s photographic record, Harry could not discern all the details of his past. It wasn’t until years later when Harry found a book written by one of his father’s colleagues about the mismanagement and treatment of teachers that Harry was able to understand what his parents went through.

“There seems to be sort of a veneer or at least a childish joy that I had because I was totally ignorant of everything that was going on around me. And the book itself was actually like, ‘this is what happened,’ and really explained that.” His parents did not tell him any stories about their time there.

As a child, his family spent downtime at a humble Indian restaurant in Karama, a residential neighborhood in Dubai. New Sind Punjab, as Harry describes it, is a bit of a hole in the wall with people packed shoulder to shoulder, eating on concrete benches. The restaurant was a place Harry’s father frequented when he lived there in the ’80s, and it became a family tradition to return. Harry’s family left the UAE in 2009, but Harry has since returned to Abu Dhabi for university. The restaurant still stands in the heart of Dubai.

“It was still nice to go to Dubai and know that there were some things that hadn’t really changed from my memories, and that was the Sind Punjab. It was a concrete representation of a bit where my family was happy in Dubai. Actually happy. It wasn’t just a facade, and it was real, and it’s still there.”

Maryam AlHuraiz: Digital Photography Breaks the Rules

How do these students react to the materiality of their images? Maryam AlHuraiz, an Emirati student at NYUAD, incorporates her family photos into her artwork. She chooses to focus exclusively on digital photography for its malleability, in contrast to the prints in family albums.

“You don’t want to touch film photos because they’re one of a kind, or they’re preserved in a way where they don’t want to get ruined. Digital pictures are kind of archival pictures, but they kind of break the rules of traditional archival pictures because I can make multiple copies of them, multiple manipulations.”

Maryam focuses on the misfired photographs such as a blurred image of her kindergarten graduation. It is unclear from the photo which of the children is Maryam, and such attempts to gather information from unclear imagery is precisely what makes digital photography interesting to her. A film photographer would not likely develop this image, but with digital cameras and smartphones, these imperfect images persist.

Maryam describes her parents’ archival processes: “They were just stored in this digital file and never printed or seen or anything. So, I was very interested in why my family never printed them nor never used them, and why they were just kept in CDs.”

With digital cameras increasingly accessible, Maryam wonders how the bygone era of photography—glossy prints and framed portraits adorning our shelves—affects how and what is photographed in the twenty-first century. Her reflections on the experience of physical albums in contrast to digital ones prompts questions that remind us of the intimacy of film and the digital malleability of our smartphone images. The differences in our treatment of these images in turn spur changes in how memories are made and preserved.

Noora Jabir: നാട്/Naddu/Homeland

What if our imagery exists across countries and cultures? Noora Jabir is from Kerala but has spent her entire life in the UAE. Her family lives in the emirate of Umm Al Quwain, and she commuted to neighboring Sharjah for high school and now lives in Abu Dhabi. I asked her how family photos reinforce a sense of belonging in the UAE.

“In general, Indians who lived here for a long time never really considered this place as their home or a permanent place to settle,” she responded. “So, it was always like, ‘oh, we’re going back.’ So, I don’t think, say, my grandad considered our photos part of the national narrative because I don’t think he saw himself as part of the nation. For me, I guess we are a huge part of the nation. And the photos definitely say that.”

The UN says it too: as of 2020, 3.5 million Indian expatriates made up about thirty percent of the UAE population. As a member of the Indian diaspora who has spent her whole life in the Gulf, where she is not a citizen, Noora has wondered about her true “home.” As a child, she commonly confused the Malayalam word for homeland—നാട് or naddu—for India. “It just felt like we didn’t really fit either in India or the UAE,” she described.

Almost all Noora’s family photographs have been taken in the UAE, and their archive is revealing of other histories as well. She chose to share a photo of a house for rent in Umm Al Quwain, an old childhood friend’s home. She reminisced on the friendship, which abruptly changed when she found an empty seat where her friend once sat. It is not uncommon for families to come to the Gulf and quickly leave, but there are as many expat families who have planted roots in the Emirates.

Noora detailed the phenomenon of wedding photography in Kerala—a case where family photography exists on an international stage. For Indian communities, Noora and other Malayali students explained that showing wedding photos is an important part of home visits in the Gulf. “The wedding album and the wedding video is more important than the actual wedding itself,” Noora emphasized.

For expatriate families in the Gulf, weddings typically take place back in India. Families return home to reunite, and photos serve as a souvenir. Photographs take on a dual role as documents of family events and as building blocks of narratives around the journeys between the homeland and the Gulf.

Aathma Nirmala Dious: Every Time I Saw the City, I Saw Him

Like Sreerag and Noora, Aathma Nirmala Dious is a UAE resident whose family is from Kerala, though she has spent her entire life in the UAE. Her father has worked as an architect since the ’90s and began his marriage in the Emirates in the same decade. With an architect for a father, Aathma values a sense of place in his family photos. Whether in a snapshot of her parents lounging with soda cans in an Abu Dhabi park or a photo of young Aathma at the fountain at Marina Mall, Abu Dhabi as a physical space manifests itself in her childhood memories and her family identity.

“My dad builds the buildings here. They’ll remain long after he’s gone, so he was always part of this skyline for me. Every time I saw the city, I saw him, I saw my parents, I saw my friends, family, cousins.”

Aathma’s attachment to memories of malls and family-centric spaces in the Emirates was echoed in other interviews. All students I spoke to possessed pictures of themselves at UAE malls or recreational centers that were and still are spaces of social life as much as commerce.

“Architecture here plays an interesting role in that it was built to be consumerist,” Aathma elaborated. “It was built to house temporary residents, but instead it has become such a permanent place of memory, especially malls.” According to Aathma, many Malayalam Abu Dhabi residents have variations of photos of dancing in the iconic fountains at Marina Mall.

Here we see Aathma scurrying about her family’s apartment in Abu Dhabi. Their TV setup boasts an impressive shelf adorned with thick albums, children’s art, and studio portraits of Aathma. Some elements of the space are typical of homes around the world, but such imagery carries particular significance in the UAE. Expatriate families cannot be naturalized in the UAE, nor can families retire in a traditional sense, so belonging as expressed through imagery is crucial.

Aathma rails against the perception that all expatriate families are temporary. Referring to her family photo, she proclaimed, “This is basically proof that we’ve always been here and that we’ve lived long, fulfilling, happy lives here that are not just tragedy.”

*****

The family photos shared with me reinforce a narrative of diversity that is truly at the heart of what it means to live in the UAE. These mini-archives are scattered between villas across the Emirates and one-bedroom apartments in the cities. A photo of a coy little girl from Kerala and her young, smiley mother at the memorial site of the UAE’s founder powerfully shows the multinational identity of the country. Whether marking special occasions or ordinary moments, these photos affirm that they were there, and they are still here.

Emily Broad is a curatorial intern for the UAE program at the 2022 Smithsonian Folklife Festival. She received her BA at NYU Abu Dhabi and will be pursuing a PhD in visual and cultural studies at the University of Rochester. Her research focus is family photography.