Remembering E.O. 9066: San Jose Taiko on Musical and Historical Resonances

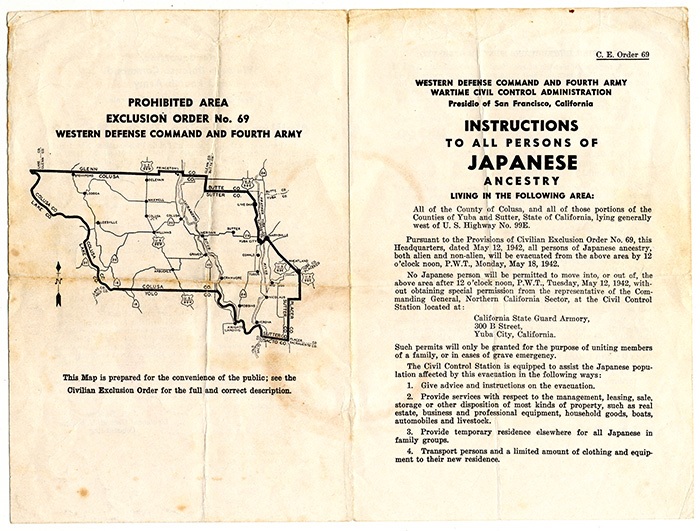

February 19, 2017, marked the 75th anniversary of President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s signing of Executive Order 9066, which authorized the exclusion of Japanese Americans from the West Coast during World War II.

Starting in February 1942, in the aftermath of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor and without due process, entire communities, both American citizens and their immigrant family members, were forced from their homes. Approximately 120,000 people were subsequently incarcerated in inland camps during the war. Japanese Americans were not permitted back on the West Coast until 1945, and the damaging force of the executive order endured well beyond the time it took some communities to physically and economically rebuild.

Four decades later, the United States government formally acknowledged “the grave injustice” of its actions, describing them as the result of “racial prejudice, wartime hysteria and a lack of political leadership” in the Civil Liberties Act of 1988. This legislation issued a national apology and reparations—culminating a movement mobilized by community activists, a bipartisan congressional investigation, and a successful Supreme Court ruling in favor of those who had earlier challenged the exclusion order and curfew.

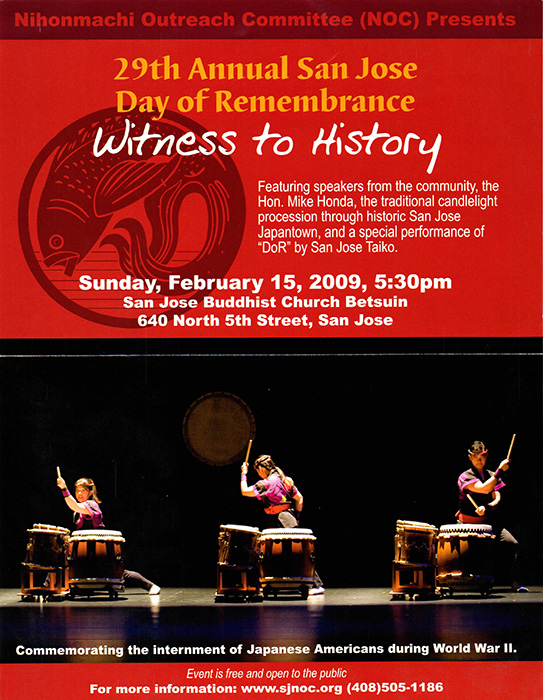

Since the late 1970s, Japanese American communities have organized annual events on the anniversary of the signing of E.O. 9066 as a means for recovering a marginalized history and educating the public about the legacies of the exclusion experience. “Days of Remembrance” (DoR), as they are called, are now observed in as many as twenty cities, including Washington, D.C., where the Smithsonian has produced an event nearly every year since the early 2000s.

In honor of the Day of Remembrance and in anticipation of this summer’s American Folk program at the Folklife Festival, we talked with San Jose Taiko, whose former leaders Roy and PJ Hirabayashi are NEA National Heritage Fellows. Founded in 1973, San Jose Taiko was among the pioneering ensembles in the United States to reinterpret Japanese drumming traditions into a dynamic and particularly American artistic expression.

The first American taiko groups were formed in the late 1960s and early 1970s. They emerged from the activism and protest movements of the time and out of the challenging decades of their communities’ post-war resettlement and recovery. For many, taiko provided a means for reclaiming aspects of their Japanese heritage, which had been a source of marginalization and shame after World War II.

In 2011, Roy and PJ handed over the reins of San Jose Taiko to longtime members Wisa Uemura and Franco Imperial. They remain involved with the group and the broader taiko community. Both are active as teachers and artists—leading master classes and workshops, performing as a duo, and working on their own projects.

On the eve of the 2017 Day of Remembrance, we asked Roy, PJ, and Franco to share their reflections on the meaning of the day—how it relates to their personal experiences and the role of art in building community and social justice.

What is taiko in America? What has it meant for you?

PJ: Taiko is a cultural expression that embodies all of our experiences of having grown up here in America. When I got involved in the 1970s, taiko was about the experience of Asians in America who were finding that voice. It provided a place for us to discover who we are and who we could be. Taiko spoke so vigorously to me because I felt like there was a sense of empowerment through the energy.

Growing up, I could not find anything in the cultural arts for me to tap into. I couldn’t get into classical dancing. I couldn’t get into flower arranging or tea ceremony. Taiko encapsulated the physicality of sports, martial arts, dance—the movement, the musicality, the discipline, the theatrics— everything that could just make me very ballistic and very open.

Roy: We realized early on that we were an Asian American group. What is Asian American music? It’s what we listen to every day—Latin, R&B, jazz, soul music. All that was a big influence on our musical style and what we were trying to do.

Also for us, then and now, taiko is more than an instrument, more than just music. When you play the drum, it’s not just creating a sound, but it’s the whole environment around you. It’s about everything involved in creating that sound. Not just the stick, not only the drum, but it’s the hide that’s on there, and where that came from, and how that drum was put together, and how you work together with other people within the ensemble.

San Jose Taiko is based in one of the three remaining historical Japantowns in California. Why is a sense of history important to your work?

Roy: Understanding history fosters our capacity for gratitude and responsibility. History provides us with a foundation for understanding and awareness.

PJ: The civil rights, antiwar, and ethnic pride movements in the late 1960s and 1970s helped frame my awareness of my parents’ World War II incarceration in Poston (Colorado River), Arizona, and the disintegration of our nuclear family. I remember my parents referencing “camp” throughout my childhood, but I thought they were referring to a summer camp. When the redress movement was in full force, I heard our elders’ stories of hardship presented at senate hearings, how mass incarceration impacted their lives, and the unconstitutionality of the executive order.

The history of my community’s World War II incarceration has been a piece in exploring my cultural identity and finding my personal power. Hearing the taiko for my first time in the early ’70s was the visceral wake-up to my cultural past, to personal and collective self-expression as Japanese American/Asian American, and the potential of a new cultural and community movement: taiko!

What is the significance of Day of Remembrance for you?

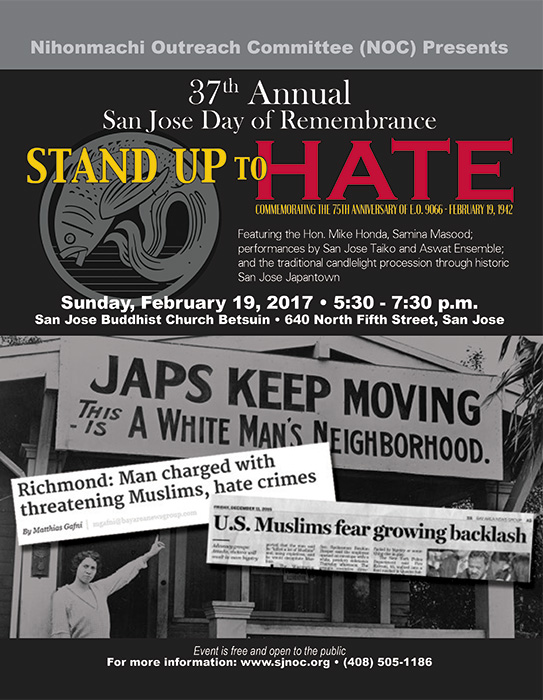

PJ: When the first Day of Remembrance events were being commemorated in the late 1970s-80s, I felt a deep sense of vindication and empowerment. When the Nihonmachi Outreach Committee organized the event for our San Jose Japantown community, it was the first time for me to witness the Japanese American intergenerational community rally en masse around civil rights. Wow!

Roy: Over the past thirty-seven years, San Jose Taiko has participated in almost all of the San Jose DoRs. It has always been a high priority in our performance calendar. The event aligns with our group’s core values of connecting to the local Japantown community— past, present, and future—and bridging communities for cultural exchange, and cultivating solidarity in co-created action.

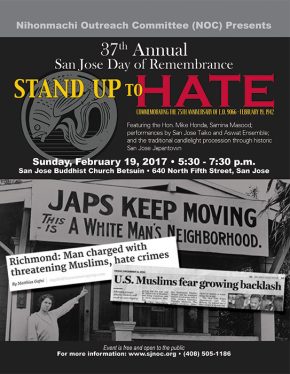

Since September 11, 2001, the San Jose DoR has stood with the Muslim community to show support in face of what is happening to their communities—a repeat of what happened in 1942 with hate crimes, racial profiling, talk of internment, and now the banning of travel.

San Jose Taiko regularly performs a song called “DoR,” composed by Franco Imperial. How did this come about?

Franco: At the 2004 San Jose DoR, Islamic Networks Group founder Maha Elgenaidi was a guest speaker and shared how it was the Japanese American community who had first come to the aid of the Muslim American community post-9/11, when hate incidents began increasing. It dawned on me that Day of Remembrance, an event that had been occurring for decades, no longer was solely a warning from the past. The larger impression on me was the idea of cultural communities standing up for one another.

The founders of San Jose Taiko chose the drum as a way to explore and express who they were as Japanese Americans/Asian Americans. I wrote “DoR” in 2007 to put myself on a similar path of exploration and expression. I wanted to create something that celebrated the support of communities versus the darkness of hate or fear. It was meant to be about hope and compassion.

Any last words on the 75th anniversary of E.O. 9066?

Franco: At this year’s Day of Remembrance, San Jose Taiko is presenting Aswat Ensemble, the premier Arab music ensemble in the Bay Area. They will be performing a set of their own, and then their principal percussionist will play with us during a candlelight procession through Japantown. Our aim is to celebrate the support between Japanese American and Muslim American communities through music inspired by a shared history of being on the receiving end of hate and fear—to demonstrate the role of art to build bridges of understanding and support.

Members of San Jose Taiko and Aswat Ensemble provide accompaniment during the 2017 candlelight procession through Japantown. Congressman Mike Honda, his granddaughter, Richard Konda of the Asian Law Alliance, and Caroline Kameya from the Nihonmachi Outreach Committee carry the banners at the head of the group. Video courtesy of San Jose Taiko

PJ: Taiko’s presence at DoR lends an uplifting energy of joy and hope coming out of a dark past. Taiko’s vibration stirs the heart to open. I don’t regard it as just a drum, a musical instrument. It’s a powerful tool for bringing people together.

PJ and Roy Hirabayashi will be participating in the American Folk program at the 2017 Smithsonian Folklife Festival. For more information about the history of Japanese Americans during World War II, visit the National Museum of American History exhibition Righting a Wrong: Japanese Americans and World War II, on view until February 19, 2018.

Sojin Kim is a curator at the Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage.