Sharing California’s Cultural Treasures

Last month, the Smithsonian Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage hosted the symposium Cultural Sustainability in the Age of Globalization along with the Alliance for California Traditional Arts and the Royal Textile Academy of Bhutan. The event featured community activists, folklorists, scholars, and traditional arts experts exploring efforts to sustain local artistic practices and cultural identities in the face of globalization.

One of the presentations was from Amy Kitchener, executive director and co-founder of the Alliance for California Traditional Arts. ACTA was established in 1997 by cultural workers, arts administrators, and traditional artists. Its mission is to support ways for cultural traditions to thrive now and into the future by providing advocacy, resources, and programs for folk and traditional artists. Over the years, it has supported over 1,000 grants and contracts to further traditional arts practice and sharing.

ACTA brings its valuable breadth and depth of work in California to this summer’s Sounds of California program at the Folklife Festival. After the symposium, Kitchener explained more about ACTA’s work, community engagement practices, and some of the artists who will be featured on the National Mall this summer.

What is the role of traditional arts in building a healthy community?

The notion that traditional music can bring people together is not new. Skilled artists are able to adapt their music to bring people together. Our job is to figure out how selected cultural treasures can be brought to bear on policy as well as access to resources.

For example, César Castro, a master of son jarocho music and dance, led community workshops to teach collective song composition in support of a campaign to legalize street vending in Los Angeles. This campaign was significant because street vending provides an important small business opportunity for the large population of Mexican immigrants—some of whom do not have working papers, but have traditional cooking skills.

This activity did not function as propaganda. Instead, it was a bottom-up approach for community members to formulate public statements around the issue.

What do you think about artists incorporating diverse influences into their own music traditions?

First of all, traditions are constantly changing. California is home to hundreds of diverse traditions and to an incredibly diverse immigrant community. People living in the same community are often from different cultural backgrounds. And it’s inevitable that people will be influencing one another.

We are lucky to have brilliant musicians who are able to use their musical traditions as bridges to connect to other communities. They may introduce new sounds, but they can also stay faithful to the cultural values of their own traditions.

Social context and audience members are really important factors in determining how traditions change and adapt. I am thinking at the moment about the Pilipino-American musician Danongan Kalanduyan. He has been recognized as an NEA National Heritage Fellow for the role he has played in spreading the kulintang (bronze gong and drum ensemble) tradition of his home region of Mindanao to Pilipino communities in the U.S. It is interesting to note that this music, rooted in the Muslim culture in the southern Philippines, is now being appreciated by Christian Filipino Americans.

Since California is home to Silicon Valley, what is the impact of digital technology on traditional arts practices?

I would say technology has largely facilitated, not hindered, people’s ability to transmit their musical traditions. This is a big question, a complex situation—but I can give you an example. We have a master-apprentice program. We can see that technology makes it possible for students to learn traditional music from teachers in their home countries. Several apprentices in our program are doing this through Skype.

Technology also provides the means through which community members stay connected. Grupo Nuu Yuku, a Mixteco dance group from the San Joaquin Valley, will perform at the Smithsonian Folklife Festival this summer. The group members are on Facebook all the time. In fact, Diego Solano, the group’s co-director, told me that when they posted about their invitation to the Festival, he was contacted by a mask maker in his hometown of San Miguel Cuevas, Oaxaca, volunteering to accompany the group to Washington, D.C.

In many towns of the Mixteca Baja, where the group members come from, most of the men have left in search of work in other parts of Mexico, the U.S., or Canada. The majority of people left behind are either children or elders. The internet helps these separated families keep connected.

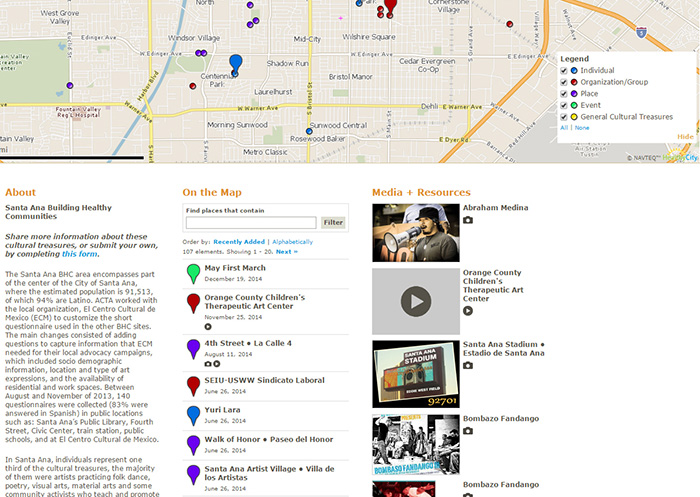

Can you explain your cultural asset mapping project in rural California communities?

The idea behind this project was to identify people, groups, places, and events—what we called “cultural treasures”—that were considered to be culturally significant. In each community, we created questionnaires that community members could submit online or on paper. We kept our methods flexible—specific to the particular place and situation.

To document responses, we recorded interviews and took videos and photographs. During the interviews, we trained residents how to identify local treasures. Some of the questions we would ask included: 1) Do you have any skills based on your heritage that you found valuable to your community? 2) Can you name any groups or organizations that give you a sense of community or a sense of being at home? Such a process naturally led to conversations where community members had to think about what to feature.

Then we created an inventory comprised of the community’s submissions describing who and what they considered to be local cultural treasures. Finally, we made our research visible through organizing a public celebratory event in each site.

What has it been like collaborating on the Sounds of California program?

It has been a beautiful thing to have this trilateral partnership among the Smithsonian Folklife Festival, ACTA, and Radio Bilingüe. Each of us cannot achieve the same scale of work alone. There are a number of participants coming to the Festival whom we have worked with over the years. Some have been ACTA grantees and students in our apprenticeship program.

We are not only excited about the upcoming program at the Festival but also in planning ongoing work to promote the sounds of California in the long run.

Ying Diao recently graduated from the University of Maryland, College Park, with a Ph.D. in ethnomusicology. She is currently an intern for the Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage and the Sounds of California program at the 2016 Folklife Festival.