George Abe: Ripples of Japanese Internment

George Abe is an energetic, enigmatic man. A Japanese American born and raised in California, he presented and performed as part of the Sounds of California program.

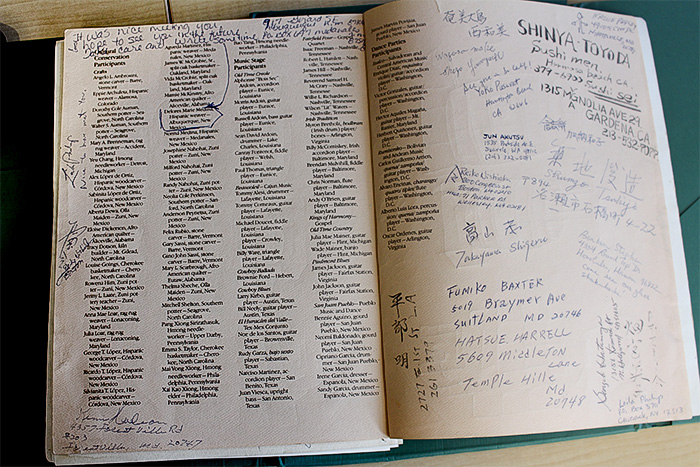

This was not his first time at the Folklife Festival—he also came in 1986 for the Japan program that was featured alongside Tennessee. When looking at his Festival program book from that year, his personality exudes from the pages filled with personal goodbyes and notes from people he had met.

“To the pied piper, Great having another L.A. fellow around!

Con mucho carino, Alicia”

“Geo—It was such a pleasure meeting you and we look forward to seeing you again.

Remember—Maryland is for CRABS, Hank”

“A high point of my life was coming to the 1986 Festival,” George reflected. “I felt like I was really in my element because I could speak Japanese, so I could talk to the forty some people here from Japan, but I am also an English speaker, so I was talking to the Grand Ole Opry guys too. The fiddling, mandolining, banjoing, and the parties—the mixing was awesome.”

Thirty years later, he returned as a member of FandangObon, a Mexican-Japanese collaborative performing arts project from Los Angeles. The group combines and connects the participatory music and dance traditions of fandango son jarocho of Veracruz, Mexico, and the Japanese Buddhist ritual of obon.

Having grown up within a community of Japanese artists and musicians, George was infused with creativity from an early age. Despite the hardships that his family and community faced, he emanates positivity, always playing devil’s advocate—nothing is purely bad or good.

This interview with George was interspersed with poetry, bamboo flute, and meditation gongs. Sitting in the grass, under the canopy on the National Mall, he talked more about his childhood, his music, and his family influences. The poems included here were written by his mother, Satsuki Abe.

What was your childhood like?

I was born in Manzanar, California, about seven miles out of Lone Pine. It was an internment camp, a concentration camp, during World War II. My mother moved from San Pedro. My father was in Los Angeles when he was relocated. They married in camp, and I was born in camp.

***

Apricot flowers in full bloom

We come to this small town

To start a new life together

Mother and child

***

I grew up as kind of a nisei—second generation Japanese American—but kind of unusual in that my mother was born in America, but my father was born in Japan. So I am in between culturally. My first language was Japanese, baby Japanese. Then going to school, and with my friends, I spoke English. But I was rooted in Japanese culture.

Because my parents were both artists, the milieu that I grew up in were poets, musicians, people very connected to the associations. From growing up in that environment, there was a word that kept coming up. Through all of my life, I have been trying to understand this word. Natsukashii. I guess the easiest translation is something like nostalgia for the home country. Children’s songs, poetry, the arts, the aesthetics, all of that—you miss it when you come to the United States. So to keep that connection with the past, with that culture, they did things like shakuhachi or Japanese dance.

What do you remember about the camp?

I was a year and a half old when we left, so I can’t say that I have any memories, but I think—well, for example, my eyesight is bad. We think that is a result of camp: sandstorms and those kind of things. Some women I know, nisei women who were nurses at the time, did some research and found out that a lot of camp babies have bad eyes and bad teeth. That is because the camp conditions, the diet, the nutrient, the environment.

***

Mother and child worry

Where were they going?

Relocation was so upsetting.

Sad to think back on

***

When Manzanar first opened, it was really terrible. But eventually people started building little ponds, gardens, and they eventually built a Japanese bath. You would wash first, drain it off, and then soak, like a sauna. Cleanliness is a part of Japanese culture.

***

Soaking in a hot bath

Washes away care and worry

It’s so refreshing

I almost forget I am a prisoner

***

What was your mother like?

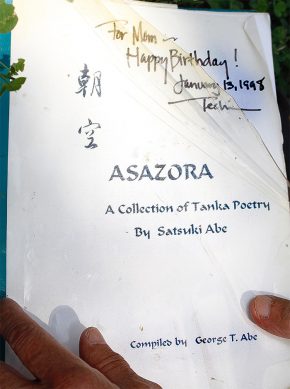

My mom was a poet. She wrote tanka poetry, which is a Japanese form of poetry that goes back to 800, 900 AD. My mom used to say that Japan is a land of poetry, and it’s true. In my mom’s case she was born here but educated in Japan, so I think for her, writing poetry was a way to stay connected to Japanese culture.

When my grandfather came here, he leased land in Orange County, the City of Orange. He had a farm, and they apparently made some money because they went back to Japan. My mom, at that time, was in the fourth grade. So that was very dislocating. She got teased a lot.

At age twenty-six, she came back to the United States on the invitation of her older sister. She was twenty-six years old and unmarried—very rare in Japan for a woman. I think she was very independent, and she didn’t want to be stuck in the Japanese wife role.

She ended up being a Japanese school teacher here in the United States, but that didn’t make enough money, so she ended up doing domestic work. Here she is, well educated in Japanese history, culture, and language, but she didn’t speak enough English to get a job. So she ends up doing domestic work all the way until she retired. She passed away at the age of 93.

***

Walking around

The closed down Japanese school

Even today I cannot forget

Those tears of sadness

***

My mom was an accomplished poet. Every year the emperor of Japan did a contest for poems. The emperor picks a theme, and in 1950 the theme was asakura, morning sky. Thousands of poems are submitted, and a panel of high-level writers and teachers go through them all and pick out maybe ten or fifteen poems. In 1950 my mom wrote one, submitted it, and it was accepted.

***

Bright morning sun

Moving across the sky

Brings a kind of heavenly stillness

Purifying mind and spirit

***

How did you get started playing music?

My father played the biwa, and my mother was a poet, so I grew up in a community of artists, poets, and musicians. I was inspired to play. I played clarinet and saxophone in middle school and high school. And about the time I went to college, I started digging into bamboo. Bamboo is really important in Asian culture. For example, this is a flute that I made from California bamboo grown in my friend’s backyard. And like me, it is different than Japanese bamboo. Japanese bamboo is hard and grows slowly.

Do you think of your music as a form of social activism?

Absolutely. The way I see it, there are different fronts to the [Asian American] movement. For example, we started doing taiko, the Japanese drums. It was originally in the context of the obon, the yearly festival. But one time we just started jamming. We were JAs [Japanese Americans], so nothing about that was sacred. “This is fun! This is great!”

So we started trying to make our own drums, using leather and nail barrels. We started using California oak wine barrels. We would take them apart and glue them together, using the rings to hold it together until it set. It got more and more sophisticated as time went on.

I think in Japan people really wouldn’t think about making their own drum because it is such an old tradition. But as JAs we said, we can’t afford it, but we want to do it, so let’s figure it out. So we started making our own drums. That is empowering. People would see us playing it and say, “I want to do that.”

We played at Wat Thai Temple. The Thai community is Buddhist too, but a different sect of Buddhism, but they invited us to come and play. One of the most embarrassing things you can do when you are playing drums is drop the stick. Well I got so into it, I dropped my stick. I got an ovation!

They understood, just spontaneously, that people make mistakes and have fun with it. It isn’t serious. It isn’t like I am going to die on stage because I dropped a stick. I learned a lot from these Buddhist people. Theirs is an attitude toward life that when you make a mistake, let’s celebrate it! We took this attitude and used it to learn about ourselves, who we are, how we fit into this society.

What is the purpose of cross-cultural collaboration?

The song we did “This Moment, Once in a Lifetime” is about coming together. These are opportunities for us to see the world a little differently. Otherwise you could get a little narrow.

If I practice shakuhachi eight hours a day, sure I would get good, but it’s like tunnel vision. So when I play shakuhachi with a tabla player, we are exploring a whole different soundscape and rhythm. And I grow from that.

I also really enjoy working with people of other cultures. I love doing collaborative types of things and hanging with other world musicians.

***

As a social activist and musician, George symbolizes the diverse, cross-cultural influences that have shaped—and continue to shape—California. At the Festival, he engaged with Afghan American instrumentalists, Mixteco dancers, Armenian musicians, and Basque craftsmen and txalaparta players, admiring their skill and technique, collaborating and learning. He seeks out new experiences and influences in order to grow.

SarahVictoria Rosemann is a media intern for the Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage. She has a degree in ethnomusicology, with a focus in Tibetology, and grew up in Reno, Nevada.

The 2016 Sounds of California Smithsonian Folklife Festival program was co-produced with the Alliance for California Traditional Arts, Radio Bilingüe, the Smithsonian Asian Pacific American Center, and the Smithsonian Latino Center.