La Marcha No Ha Terminado: Honoring California Farmworkers

And what should I say?

That I am tired?

That the road is long and the end is nowhere in sight?

I did not come to sing because I have such a good voice,

Nor do I come to cry about my bad fortune.

From Delano I go to Sacramento to fight for my rights.

These lyrics from “La Peregrinación” (“Pilgrimage,” 1965) by acclaimed musician and composer Agustín Lira capture a pivotal moment in this country’s labor history: the 1966 march from Delano to Sacramento, California. Spearheaded by Mexican American and Filipino agricultural workers, the movement’s leaders would eventually join to form the United Farm Workers (UFW).

In the song, Lira—a National Endowment for the Arts National Heritage Fellow—breathes lyrical voice into his life as an activist and former farmworker. He contributed significantly to the movement by producing music that mobilized the workers into action. Now a Smithsonian Folkways Recordings artist based in Fresno, he continues to chronicle the experiences and little-known histories of Chicano, Indigenous, and immigrant communities in California.

Lira will perform at the 2015 Smithsonian Folklife Festival’s annual Ralph Rinzler Memorial Concert, accompanied by his group, Alma. The lineup also includes Los Angeles-based Viento Callejero, an urban-style tropical music ensemble. The concert is Sunday, June 28, at 5 p.m. on the National Mall, in front of the National Museum of the American Indian.

Curated with the Alliance of California Traditional Arts, the concert honors the memory and legacy of Ralph Rinzler, co-founder of the Folklife Festival. Rinzler’s support for performances by “citizen artists” was unwavering and forms the backbone of the event’s commitment to promoting public engagement, fostering social awareness, and building bridges among communities. The performance is also part of the Smithsonian’s pan-institutional Our American Journey/Immigration-Migration Initiative.

The Delano Grape Strike

This year marks the fiftieth anniversary of the September 1965 Delano Grape Strike launched by the farmworkers movement. Delano—located in the San Joaquín Valley of Central California—became ground zero for the movement. Its prodigious table grape crop became symbolic of the farmworkers’ struggle when grape pickers from the area walked out of the fields and refused to collect the ripening fruit, protesting their poor wages and abysmal living conditions.

During this strike, Lira and Luis Valdez co-founded El Teatro Campesino, an organization that performed on picket lines and at union meetings to energize and bring attention to the experiences of farmworkers. The grape strike lasted five years, buffeted by national and international support from consumers, students, activists, unions, religious institutions, and other public sector entities. The effort forced major grape growers to sign landmark contracts with the UFW. As a product of the Chicano Movement, I spent many hours in picket lines during the grape strike and subsequent lettuce boycotts.

A Multicultural Movement

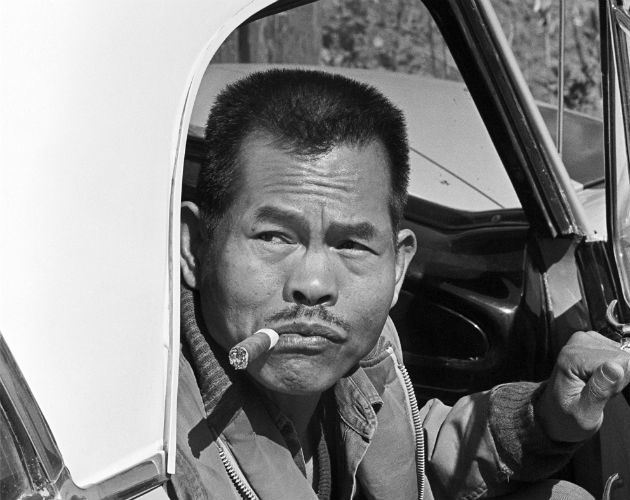

“Some of the songs I sang for the Filipinos came from the Filipinos themselves, because they sat and worked with me and taught me the verses. And we worked out the music and sang it with them together before I would go up on stage to sing.”

— Agustín Lira

It is important to appreciate the multicultural nature of the farmworkers movement. The United Farm Workers Organizing Committee (UFWOC) emerged in 1966 from the consolidation of the Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee—led by Filipinos Larry Itliong, Philip Vera Cruz, and Pete Velasco—with César Chávez’s National Farm Workers Association. The merged union later affiliated with the AFL-CIO.

Unfortunately, the role of the Manongs (the Filipino term of respect for an older man) in forging the farmworkers movement is not well documented or celebrated. In fact, 1,500 Filipino farmworkers were the first to walk off their jobs, thus launching the 1965 strike. The UFW, under the leadership of the charismatic Chávez, tended to overshadow (unintentionally, one can argue) the Filipinos’ role, as well as the participation of other ethnic farmworkers. If you are interested in learning more, I recommend watching “Delano Manongs: Forgotten Heroes of the United Farm Workers,” a half-hour documentary by Marissa Aroy and Niall McKay.

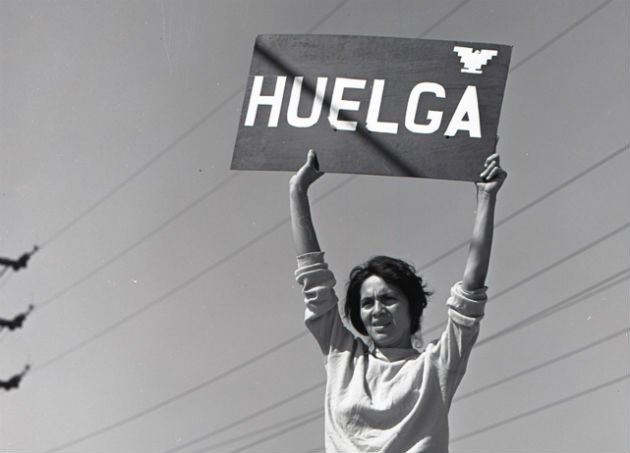

Remembering Dolores Huerta

There was a special woman who marched from Delano to Sacramento in 1966: Dolores Huerta. Huerta was the pragmatic counterpart to the charismatic Chávez. The pair co-founded the National Farm Workers Association in 1962, which became the aforementioned UFWOC in 1966 and eventually the UFW. Fearless, persuasive, and tactical, Huerta realized her vision of a better day for farmworkers, leaving her distinct fingerprints on each major UFW victory. Throughout her career, Huerta embodied new models of womanhood, inspiring generations of women activists. Today, at age eighty-five, the mother of eleven children is no less inspiring.

On July 3, 2015, the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery inaugurates One Life: Dolores Huerta, an exhibition that highlights the decisive role she played in the farmworker struggle and serves to further commemorate the fiftieth anniversary of the Delano Grape Strike. The exhibition features forty objects, including photographs, original speeches presented by her to the U.S. Congress, UFW ephemera, and Chicano art.

“Dolores Huerta has not gotten her due for the pivotal role she played in the farmworker movement, especially when compared to César Chávez’s notoriety,” curator Taína Caragol says. “Featuring her as part of the Portrait Gallery’s One Life series allows us to shed light on the life and accomplishments of this extraordinary American.”

Continuing the Fight

In coupling the Agustín Lira & Alma concert with the Dolores Huerta exhibition, the Smithsonian is able to acknowledge an important chapter in this country’s labor history by celebrating two of its notable leaders. At the same time, these programs serve to remind us that the farmworker struggle is not over. Today’s farmworkers compose sixty percent of all farm labor in this country. Despite previous labor victories, they are underemployed and subject to challenging working and living conditions. Most are seasonal workers performing tedious and back-breaking tasks, yet their pay still has them at or teetering at poverty levels (averaging $9.16 per hour). Only 28 percent have the equivalent of a high school education. According to the Wilson Center’s Migration Policy Institute, from which the above statistics were drawn, demand for labor-intensive fruits, nuts, vegetables, flowers, and other horticultural specialties will continue to rise, further impacting the lives of these workers. Presently, the estimated value of these commodities exceeds $50 billion annually.

Americans depend on the hard work and sacrifices of farmworkers and their families for large portions of our food supply. Agricultural employers are exempted from some key employment law protections, and current enforcement levels are less than desirous, leading to widespread violations in some sectors.

While we acknowledge and celebrate the accomplishments of the past, we would do well ethically to maintain a high level of awareness of present-day agricultural production and labor practices. It is important to understand that the continuing struggle of farmworkers and our own sustenance are intricately connected. Let conscience be our guide.

La marcha no ha terminado. The march is not over.

Agustín Lira will perform at the 2015 Folklife Festival’s Ralph Rinzler Memorial Concert on Sunday, June 28, at 5 p.m. Festival visitors are also encouraged to visit the One Life: Dolores Huerta exhibit at the National Portrait Gallery. The exhibition opens July 3 and will be open through May 15, 2016.

Eduardo Díaz is the director of the Smithsonian Latino Center.