Exploring with Ellie: Following the Great Inka Road

During my summer as an intern at the Smithsonian Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage in Washington, D.C., I want to soak in as much of the city as possible. Now that the Folklife Festival is over, I had time to visit The Great Inka Road: Engineering an Empire exhibition at the National Museum of the American Indian.

Museum and Festival staff worked together extensively to prepare both the exhibition and the Perú: Pachamama program. As program co-curator Olivia Cadaval said, “There was a natural link between The Great Inka Road exhibition and the Folklife Festival. The exhibition includes the artifacts and historical context, while we focused on the living culture.” Strengthening that natural link, The Great Inka Road includes many examples of how the Qhapaq Ñan (the Quechua term, translating to “beautiful road”) continues to connect modern Andean peoples with their Inka ancestry.

The Inka Empire was known in Quechua as Tawantinsuyu, “four regions together.” The Qhapaq Ñan fanned out from the main plaza of Cusco, the capital, to connect the empire’s four suyus (regions). Besides providing transportation routes, the road helped fulfill the religious goals of Inka expansion, since it linked the regions to Cusco’s central shrines and temples. Even today, travelers along Qhapaq Ñan’s route leave offerings at sacred spots called apachetas, honoring the road and the Pachamama (Mother Earth). Roadside shrines often include Catholic crosses, indicating how the area’s history has resulted in a blend of Christian and Native religions.

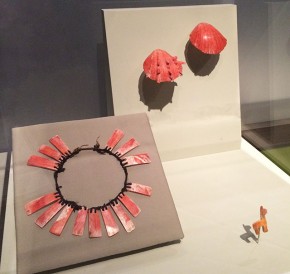

The exhibition features a variety of iconic Inka artifacts, like sacred mullu (thorny oyster shells) and flared-neck arybalo vessels used to carry chicha (fermented corn beverage). I was excited to see several examples of khipu—systems of color-coded string with strategically placed knots used to carried messages and stories in lieu of a standardized writing system.

Even the way The Great Inka Road displays these ancient artifacts pays tribute to modern communities. One display case highlighting the use of feathers in decoration features an ornament from the 1000s alongside one from the 1920s. Llama hair rope and coca leaf bags from as recently as the 1950s prove the enduring importance of ancient traditional practices.

The exhibit concludes with a section dedicated to the Inka legacy and how modern Andean people maintain connections to their Inka ancestors. Even after the Spanish invasion in the sixteenth century, people continued to use parts of Qhapaq Ñan for trade and travel. In fact, five hundred communities throughout Peru, Ecuador, Bolivia, Chile, Colombia, and Argentina still use parts of the original route. Recognizing Qhapaq Ñan’s lasting significance, UNESCO declared the road a World Heritage Site in 2014.

The most powerful part of the exhibition for me, however, was the concept of ayni, or reciprocity. In Tawantinsuyu, ayni translated to labor-based taxes called mit’a, for which a member of each Inka household worked in the holy city of Cusco for a specified period of time. Today, ayni refers to the expectation and understanding that members of a community will rely on and support one another.

I noticed evidence of ayni throughout the Folklife Festival. Performers from the Fiesta de la Virgen del Carmen de Paucartambo and Tutuma helped Q’eswachaka bridge engineers stretch and carry their rope. Delia Sallo Huaman from the Centro de Textiles Tradicionales del Cusco offered to fix a visitor’s woven bag—a souvenir from a previous trip to Peru—when she saw it had not been finished correctly.

Even though the Festival has closed on the National Mall, it leaves behind the spirit of ayni in the United States. One example is the cooperation between the Festival and The Great Inka Road. A corner of the exhibit remains empty, reserved for the Q’eswachaka Bridge that was built at the Festival. The bridge will eventually join the museum’s permanent collection, reminding us of the Inka legacy—and Perú: Pachamama—for years to come.

The Great Inka Road: Engineering an Empire will be open at the National Museum of the American Indian in Washington, D.C. through June 1, 2018.

Georgia “Ellie” Dassler is a media intern at the Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage and a student at the College of William & Mary, where she studies anthropology and teaching English to speakers of other languages.