Raise the Spirits for Ancestor Amiri Baraka

For many days to come, people of all races, ethnic groups, classes, ages, ideologies, and politics will be sharing their memories, telling their stories about some kind of special joyous or harsh occasion, experience, or relationship with Amiri Baraka, who transitioned to the Ancestors last week. For me, his life and work is summarized as a brilliant poet, playwright, freedom fighter, agitator, provocateur, Spirit Maker, friend, and comrade. When I learned he was in critical condition, I began to listen to music over the next few nights, thinking about him and his wife Amina, and the phrase “Raise the Spirits” popped into my mind.

I will not see or hear again live the smiling, dapper poet polemicist. But I have no doubt that for decades to come his voice-print will resound in the pages of an impressive body of written work and in the sound-transfer to living poets who carry his speech-DNA, his style, his social justice messages. His name will forever be associated with the linage of great freedom voices: Hughes, Baldwin, Sanchez, Madabhuti, Angelou, Walker, and others who not only spoke truth to power but who envisioned becoming another kind of humane and just power.

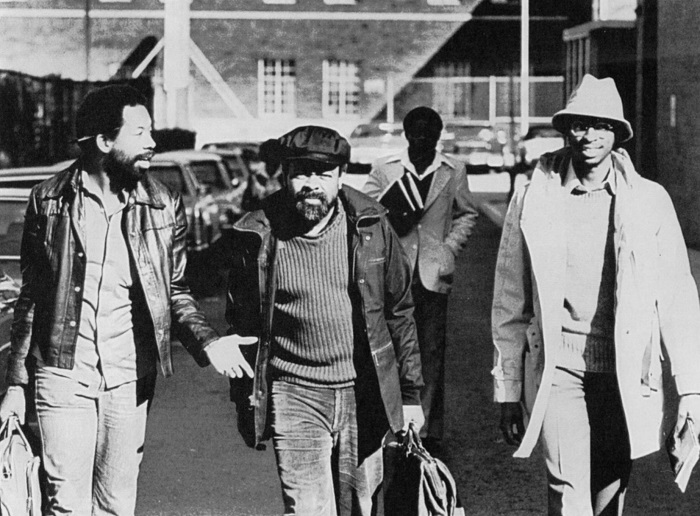

I first saw Imamu Ameer Baraka during the Pan-African Congress meeting in Atlanta when, as I recall, he and a large contingent of military-like-clad Black radicals marched down Hunter Street lined with curious observers. Around 1970 or 1971, I formally met Amiri, dressed in his African robe and hat, when Vincent Harding, founder of the Institute of the Black World in Atlanta, asked me to join them for lunch at Pascal’s Motor Hotel. Many years later, our children Miriam, Jah-Mir, and JaBen often talked with Amiri late into the night at the Atlanta Black Arts Festival, where the Poet Spirit Makers were riveted listening to Amiri’s poetic voice-messages, his dramatic imagery, his screaming rail against the history of U.S. slavery, racism, and apartheid, unabashedly expressing his (our) deep living-pain for the inhumane U.S. racism and violence against the Afro-African people.

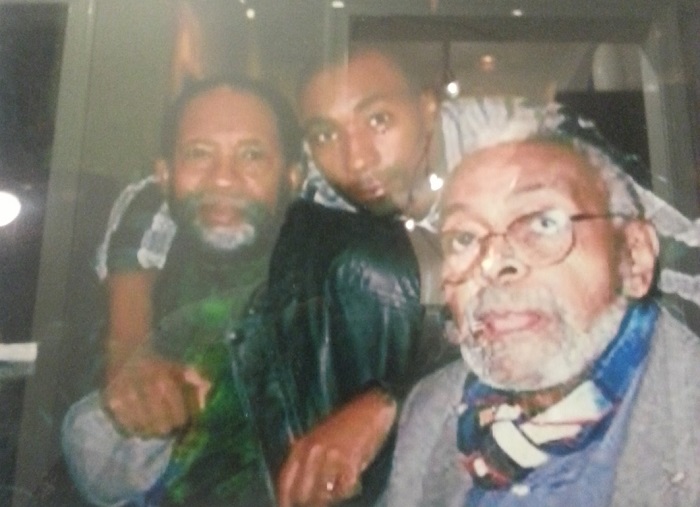

At the 1992 Atlanta Black Arts Festival, 13-year-old JaBen requested an interview with Amiri. He immediately consented and the next day said how impressed he was with the interview. They impressed each other. A few years later, while on a California trip for the National Endowment for the Humanities, I called home from San Francisco before heading to Los Angeles. JaBen said, “Daddy, you promised to take me to Newark tomorrow for the celebration of Amiri Baraka’s birthday.” I cancelled my trip, took a red-eye flight back to D.C., picked up Miriam, JaBen, and Jah-Mir from school, and rushed to Newark. We arrived at the Baraka home in time for Amina to surprisingly ask me to open comments in celebration of Amiri’s birthday.

My life-flow with Amiri was not always so relaxed and confident. Amiri Baraka in the early days that I encountered him was a towering, charismatic, imposing, for some intimidating public-space figure who would unsparingly take on you and whatever your aesthetic, ideology, religion, or politics. As a Howard University graduate student, attending an Institute for the Arts and Humanities Black literature conference, I raised my hand to speak after Amiri’s presentation. With my hands trembling and my legs shaking, I posed one of my thesis questions, informed by my budding Marxism, inferring a critique of something he had said. The Little Man Amiri Baraka, whom I had seen put down, stingingly critique his critics, looking gigantic on the stage with microphone in hand ready to rapidly respond, as was his style, looked at me in the packed audience, paused, and said something like, “Yeah, I see your point.” I had one such other occasion with him, a sign that I could always honestly approach him, share exactly what I thought, and that I would be given a hearing, even when we might disagree.

I, like many young Black people in my generation searching for individual voice and social justice ethics, learned courage and forthrightness by observing Amiri Baraka. Over the years, listening to Amiri in extraordinary readings as “poet-musician-instrument,” discussing politics, and always contrasting the intense views of his fans and critics, I came to pay more attention to the search for the core human values of people’s lives, beliefs, and aspirations for themselves and others amid the often complex, attractive, and repulsive behavior others perceive about the likes of critical, resistant, transformative voices like Amiri who would-could not be silenced. When Amiri changed his mind, his ideology, his politics, he always said so loud and clear.

No better case study, in my view, than the very public life from LeRoi Jones to Amiri Baraka to consider how and by what criteria to add up the public value of a multifaceted, at times seemingly contradictory, individual life.

Raise the Spirits.

James Counts Early is director of cultural heritage policy at the Smithsonian Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage. A long-time advocate for cultural diversity and equity issues in national and international cultural and educational institutions, his applied research explores participatory museology, cultural democracy, statecraft policy, capitalist and socialist discourses in cultural policy, and Afro-Latin politics, history, and cultural democracy.