Celebrating Spring, the Seasons, and the Sun in China

春分日

仲春初四日,春色正中分。绿野徘徊月,晴天断续云。

燕飞犹个个,花落已纷纷。思妇高楼晚,歌声不可闻。

Spring Equinox

Mid-spring on the fourth, spring hues mark balance.

In green fields stroll moon, blue sky dotted clouds.

Swallows one by one, petals drop by drop.

At night missing wife, hear not singing voice.

This poem by Chinese poet Xu Xuan (徐铉) (916-991 CE) honors the transition from winter to spring. According to the Chinese Almanac, March 21 is the first day of the season—despite the still-snowy forecast here in Washington, D.C. At the vernal equinox, the sun passes the earth at zero degrees longitude and day and night are equal lengths. Ideally we emerge from winter and begin to thaw.

In the United States, we are likely familiar with the equinoxes and solstices and their correlations to Paganism and the Western zodiac. But in China and other East Asian countries, these events on the lunar/solar calendar are also significant to farm life and folk traditions.

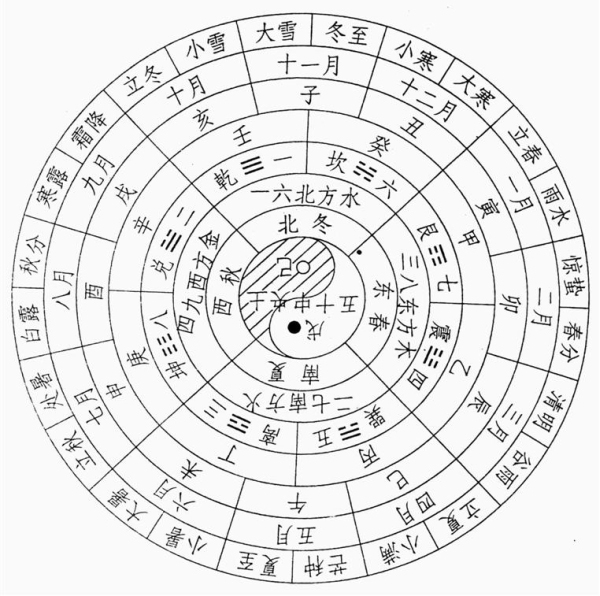

Spring Equinox is one of twenty-four solar terms that mark every fifteen degrees on the sun’s ecliptic path. The terms have fun and climatically descriptive names, like Insects Awake (Jing Zhe 惊蛰) as life comes out of winter hibernation, Clear Bright (Qing Ming 清明) in the height of spring, Hidden Heat (Chu Shu 处暑) as summer fades, and Big Chill (Da Han 大寒) closing out the year’s cycle in the dead of winter.

Each term is divided into three parts, also denoting biological and botanical phenomena. Spring Equinox (Chun Fen 春分) consists of the rather cryptically titled “dark birds arrive” (swallows migrating north), “thunder sounds” (beginning of spring storms), and “lightning begins” (double entendre for thunderstorms and gradual lengthening of daylight).

Chinese farmers, particularly in the Yangzi River Delta region, traditionally used these terms to plan planting and harvesting schedules. Outside of agrarian societies, the terms are more of an archaic novelty, but they still suggest a deeply rooted connection to nature and the land in China.

On Spring Equinox, farmers in China have a tradition of taking the day off and eating sticky rice balls. Additional rice balls with no filling are stuck on long bamboo skewers and placed around their fields to prevent birds from eating at their crops. This practice is called “stick the bird’s beak.” Another Chinese tradition—though originally associated with Lunar New Year then popularized in the United States on the equinox—is attempting to balance an egg upright, demonstrating the equal balance of day and night and the harmony of nature.

In 2011 Beijing reinstated a five hundred-year-old Spring Equinox tradition, a ritual sacrifice to the sun. Among dancers and musicians, a volunteer “emperor” offers jades and silks and attendees offer prayers to the sun deity, the God of Brightness. Equinox events like this, in China and all over the world, celebrate ancient traditions and significance of the sun and the seasons in both rural and urban life.

At the Smithsonian Folklife Festival this summer, China: Tradition and the Art of Living will present traditional and contemporary Chinese activities related to seasonal festivals. Come visit to experience a one-year cycle of celebrations from Spring Festival couplet writing to New Year’s paper cutting, Clear Bright kite flying, and Dragon Boat Festival sachet making.

And until then, enjoy the spring!

Elisa Hough is the editor for the Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage. This is her first East Coast winter and she is desperately wishing the weather would catch up to the calendar.

Program assistant Joan Hua contributed to this article and translated the above poem. Information on the solar terms comes from the 2014 Pocket Chinese Almanac, translated and annotated by Joanna C. Lee and Ken Smith, advisors to the China program.