Exploring Endangered Languages

I’m approaching the day when I must leave school and make my way in the world; as a graduate student, I’ve been asking myself on a daily basis, “What am I going to do now that I’ve grown up?” Because I’ve been a student since age six, the prospect of leaving school is a little terrifying.

Luckily, I was able to spend six months interning at the Smithsonian Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage, where I had a wide range of duties: I conducted ethnographic research, helped out with regular office tasks, built a Mexican tortilla oven, and moderated at the 2013 Smithsonian Folklife Festival.

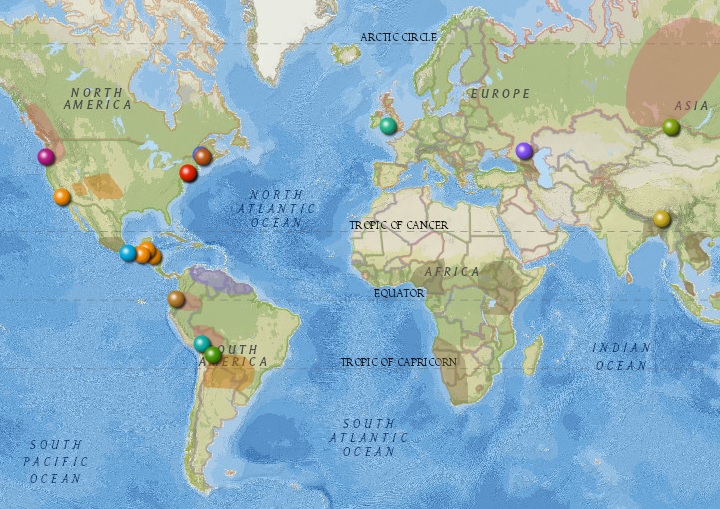

One major project I worked on is an online interactive story map, featuring endangered languages around the world, created in connection with the Festival program One World, Many Voices: Endangered Languages and Cultural Heritage. I collected photos, videos, and audio files from language communities all over the world, wrote brief informative narratives about the featured groups, and learned about language and culture through detailed field reports and months of research. My academic and ideological interests lie in linguistics and cultural studies, and it was a great experience for me to work on a project that so closely connected language and culture.

One key challenge I faced while compiling materials for the map was determining what content should be included on the map and how. We did not want to misrepresent the cultures featured, and I felt responsible for presenting their languages and cultures in an informative and respectful way. Additionally, with every bit of information we added to the map, there were thousands of interesting and important pieces that were left out.

While working on the Endangered Languages Story Map was exciting, the most rewarding aspect of working on the One World, Many Voices team was finally meeting all the fantastic culture-bearers that I had encountered through my map research. At the Festival, I worked closely with a delegation of five Koro speakers from Arunachal Pradesh in the northeastern corner of India, facilitating conversation and exchange between the Koro and visitors to the Festival. The Koro-Aka language was not officially acknowledged until 2008, and only about 600 to 800 people speak it.

Despite my research, I did not feel I knew much about this group before presenting with them at the Festival. Every day we spent together we talked about their language, culture, religion, daily life, taste in music, and food. I quickly gained a much better understanding of the Koro people and the connection between their language and culture.

During the Festival, getting visitors engaged with participants was one of the most important challenges I faced. Similar to the issues of representation I tackled while working on the story map, I did not want the Festival visitors to just look at the Koro people’s “otherness” and admire their crafts. I wanted them to interact, communicate, and explore what aspects of our lives are actually quite similar, what our cultural differences are, and why they are important.

Although the One World, Many Voices program focused on endangered languages, many visitors could not grasp what it would be like to lose their language. We spent a lot of time discussing what language means to people and to their culture, which I found enlightening. For those of us who are not at risk of losing our language, I don’t think there is an awareness of how language shapes identity, informs the practice of cultural traditions, and impacts relationships with family and friends.

Meeting culture-bearers and language activists at the Festival helped many visitors think more critically about the intersections of language and culture. It certainly impacted my perspective: I am not a native English speaker, and, though I speak it fluently, I never feel like I’m the same person speaking English and Danish, my mother tongue; I never understood why. This program helped me understand how culture and languages indeed are living, however intangible, pieces of identity, at the core of our existence.

So far, I’ve written a lot about “realizing” and “understanding” things, but boy did the Festival experience create questions as well! How do we present these cultures while meeting the needs and interests of the participants, the Smithsonian, and the audience? What if participants want to sacrifice a living animal on the National Mall as an important part of a cultural tradition performed in their native language? How do we avoid “museumizing” and exhibiting these people? How do we “preserve” a language that is still living, evolving, and transforming? How do we engage participants and visitors effectively?

I am not out in the world beyond my university doors just yet, but after interning on the One World, Many Voices program, the post-student life doesn’t seem that scary anymore, and I know exactly what I will write my master’s thesis about. Working closely with the CFCH team and the culture-bearers at the Festival has given me a lot of ideas about how to work with preserving living cultures—ideas I hope to test myself one day.

Anne Sandager Pedersen is a graduate student at University of Copenhagen, Denmark, pursuing a degree in modern culture and communication. Anne is currently doing further research for the Endangered Languages Story Map, and writing her master’s thesis about how to preserve living cultures through the Smithsonian Folklife Festival.