Face Jug

A shift from utilitarian to decorative wares

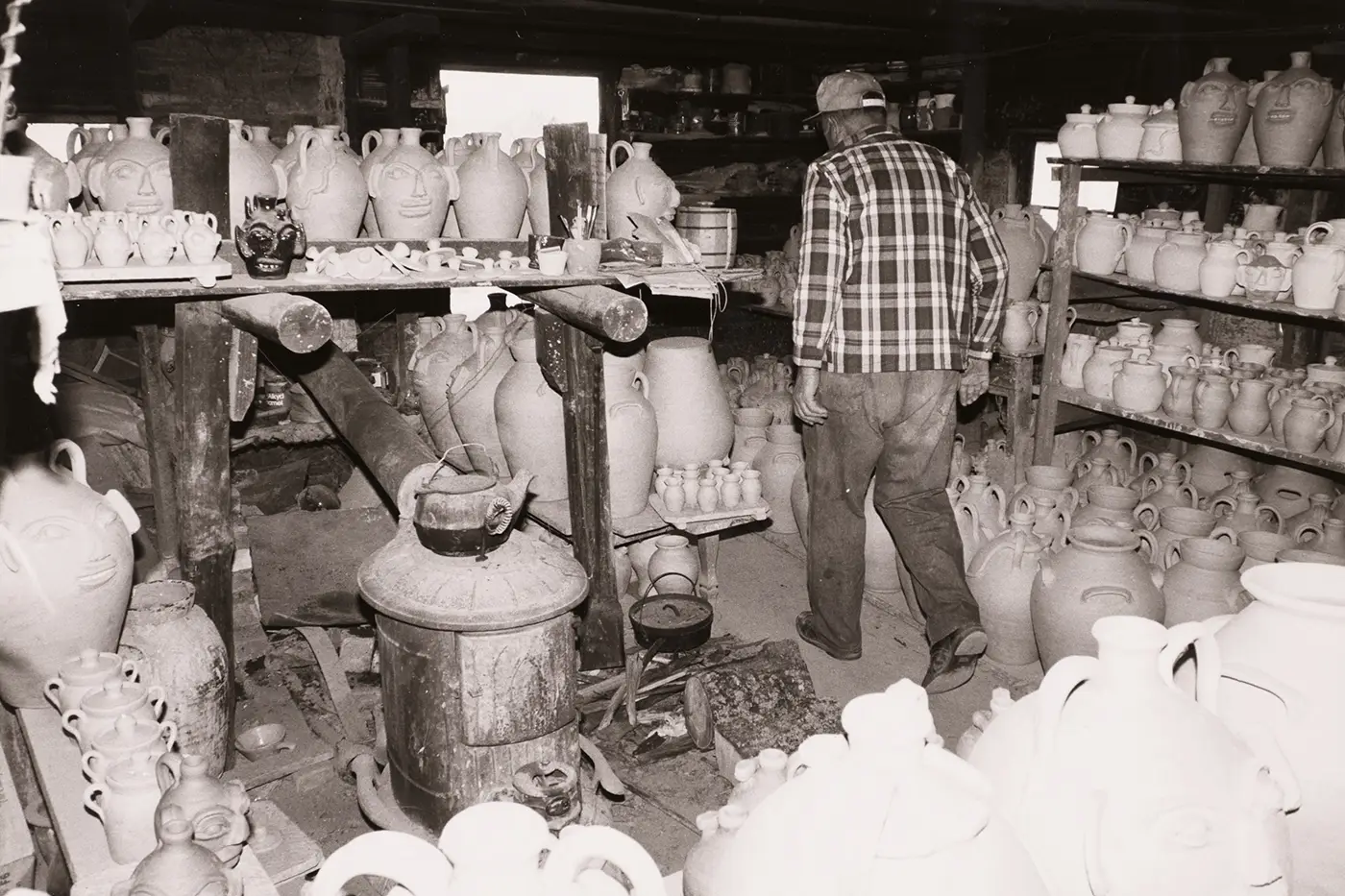

The pottery market in the Catawba Valley region of North Carolina was shifting in the first half of the twentieth century. The introduction of mass manufactured food storage containers and refrigeration stalled the market for utilitarian wares, leading potters to experiment with more decorative styles. “Swirl ware” emerged in the area around 1920 and became so popular that many artisans, like Burlon Craig, began replicating its style. To create the swirl effect, Craig layered two colors of clay before “turning” or throwing the piece on the wheel. The swirls emerge as the body of the pot is raised. Once it dried to a leathery texture, Craig added facial features and then fired the ware.

Craig speculated to folklorist Charles Zug (in the book Turners and Burners) that his dislike of making swirl ware was shared by other potters: “I don’t think any of them really liked to make [it]” because of the extra time involved, “but it would sell.” He also noted that while he did not like decorating face jugs, he approved of their “modern efficiency:” They earned higher profits without taking up additional kiln space.

Craig used a “groundhog” kiln to fire his wares. These kilns, staples in Catawba Valley pottery, are constructed mostly underground and burn wood as fuel. The regional style used alkaline glazes, made of combinations of ash, crushed glass, and clay slip. While participating in the 1981 Folklife Festival, Craig was acknowledged as one of the last potters to continue the traditions of the area. He received the prestigious National Heritage Fellowship from the National Endowment for the Arts in 1984, and his rising fame sparked wider interest in Catawba Valley pottery.

Today, the Catawba Valley boasts a small group of potters following in Craig’s footsteps. Despite viewing himself humbly, Zug proclaimed that Craig and his wares “touched so many lives … across the nation.”