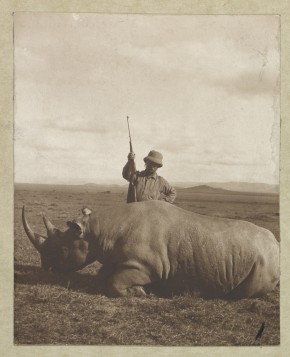

Theodore Roosevelt in Kenya

Before there was a Folklife Festival, before the Smithsonian research centers spanned from New York to Belize, and before presidents were supposed to retire quietly to found libraries and nonprofits, Theodore Roosevelt was restless.

This year marks the hundred and fifth anniversary of the twenty-sixth president’s expedition to Kenya and eastern Africa, where he traveled and hunted big game with three Smithsonian scientists and his son Kermit Roosevelt, also the expedition photographer. From 1909 to 1910, Roosevelt and his crew trekked through Kenya, Uganda, the Congo, and southern Sudan, exploring, shooting, and capturing footage and photographs that museums still treasure today.

Part of the Smithsonian’s motivation for co-sponsoring the expedition was to obtain specimens for the new United States National Museum building under construction on the National Mall—the building would later be renamed the National Museum of Natural History.

The Smithsonian sent along naturalist Edgar A. Mearns as organizer and bird collector, zoologist Edmund Heller to prepare large game, and zoologist John Alden Loring to collect and prepare small mammals (Kermit noted in his photography records that “Loring is called wanna panya [from the Swahili words for gentleman and mouse] by the [natives].”)

With the help of two big game hunters and over 250 African porters, they brought back more than 5,000 lion, rhinoceros, elephant, giraffe, hyena, zebra, warthog, and other mammal remains from East Africa, comprising over 160 species. Combined with the 18,000 specimens of plants, birds, and cultural objects from local tribes and communities, expedition acquisitions were enormous. Early taxidermy techniques meant the scientific team also traveled with several tons of salt for preserving skins—but they still managed to find room for Roosevelt’s personal traveling library of several dozen books.

It was not the first time the outdoorsy politician had expanded the Smithsonian collection; while he was still in his twenties, Roosevelt donated his childhood natural history “museum” to the Smithsonian, which included nearly 250 specimens. Some were as exotic as birds from the Nile River Valley that he had collected at age fourteen while on a trip to Egypt with his father.

Kermit’s photographs show a keen interest in all sides of the African landscape. Besides recording animals from puff adders to wildebeest—not all of them trophies—he also took candid shots of the herding, dances, and daily life of the Maasai and other native communities that the party crossed paths with. Wildlife photographer Cherry Keaton recorded the same scenes on an early hand-cranked camera, and the footage was later made into the silent film Theodore Roosevelt in Africa, most of which is available on Youtube.

The trip that had started in Mombasa, Kenya, came to a close in Khartoum, Sudan, in 1910. Before returning to the States, Roosevelt and Kermit made a brief stopover in Oslo, Norway, to pick up the Nobel Peace Prize the former president had won four years earlier for his help in negotiating an end to the Russo-Japanese War.

Today, Kermit’s photographs are preserved in the Library of Congress, the Smithsonian Archives, and the Theodore Roosevelt Collection at Harvard College Library. His father’s beloved Springfield rifle resides in a glass case in the National Portrait Gallery’s Hall of Presidents, under a selection of pictures from the expedition. The only animal specimen from Roosevelt’s Kenyan adventure still on display is a single northern white rhinoceros, which kneels quietly in a glass case in the new Kenneth Behring Family Hall of Mammals in the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History.

Fittingly enough for Roosevelt, it’s next to a bull moose.

Meg Boeni is a media intern for the Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage, who studies journalism and Spanish at Boston University. Her favorite story about TR is about how his daughter Alice liked to surprise guests with her pet snake, Emily Spinach, at White House dinners.

For more about Smithsonian expeditions and the Roosevelt connection, please visit the NMNH website and the Library of Congress online. Many of the films recorded of Theodore Roosevelt are also available for free from iTunes, courtesy of the LOC.